Blog

Article List Home My Research Services Contact Me

|

Wilkes: Bauguess, Yates, Hall, Bunker,

Civil War April 29, 2021 Letha Yates Bauguess and Reuben

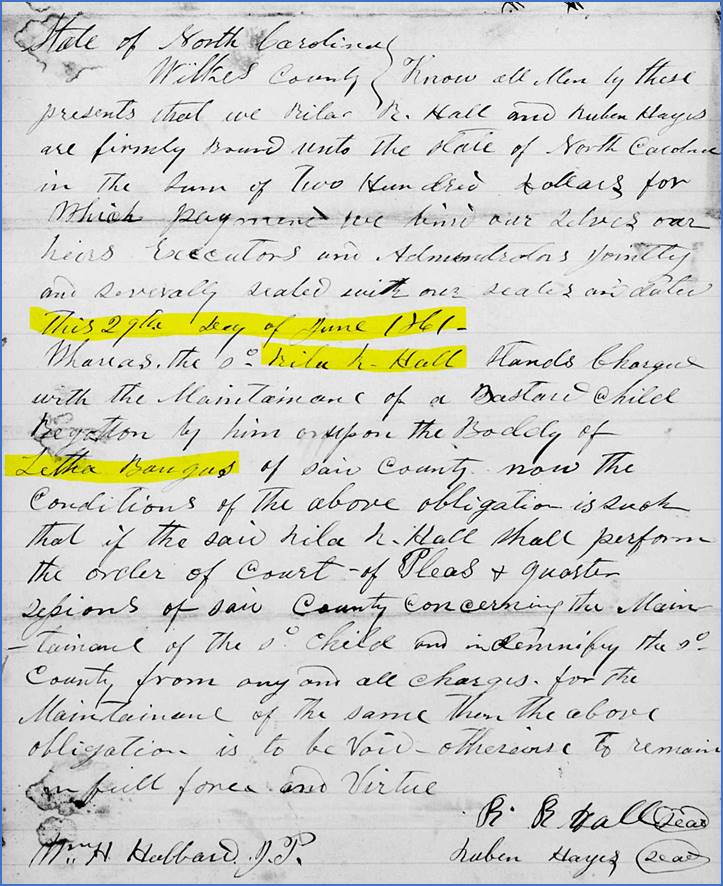

Riley Hall In February of 1861, Letha Yates Bauguess

was mentioned in a court bond that stated she had given birth to a child and

that the child’s father was Reuben Riley Hall. Letha was the widow of Samuel J. Bauguess,

and on June 29th, Riley was charged with providing for the maintenance of the

child. The name of the child wasn’t given, but

perhaps she was the 3-year-old Almeda Bauguess who was listed with Letha in

the 1860 census. If Almeda was the

unnamed child, then why did it take three or four years for the court to

charge Riley with providing for it?

The alternative is that the child was born after the 1860 census was

taken in June of that year and before the February 1861 court record. No other records have been found for Almeda

Bauguess who was born about 1857, and nothing has been found to indicate that

Letha had a child who was born in late 1860.

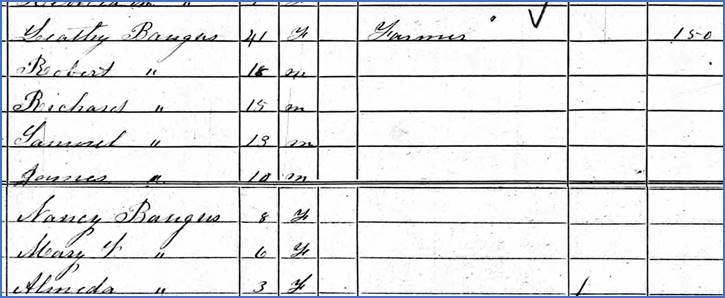

1860 Wilkes County

census: Letha Bauguess Behind every old record or court

document, there is a story to be told.

It’s easy to simply see the names and dates and move on, but taking

the time to get to know our ancestors makes them seem more real and

relatable. So who were these

people? What was going on in their

lives at this time, and what became of them later? Letha was born in 1820 to David Yates

and Nancy Hayes, probably in the Rock Creek area of Wilkes County. She was one of at least five children, and

her two younger sisters, Adelaide and Sallie, became the wives of the Siamese

Twins Eng and Chang Bunker in the spring of 1843. In fact, that double wedding took place in

the Yates family home. The wedding did

not take place in a church because the girls’ mother Nancy could not travel

due to her weight. She was said to

weigh over 500 pounds. Most likely Letha attended her sisters’

wedding with her husband Samuel J. Bauguess whom she had married three years

earlier in 1840. They likely attended

with their infant son Robert. Over the

next eleven years, Samuel and Letha would have five more children with their

youngest daughter Mary being born in 1854.

But during that time, tragedy struck the Yates family when Letha’s

mother Nancy died in 1850, likely before she had reached the age of 50. Her widowed husband didn’t stay single for

long. On April 26, 1851, he married a

much younger lady named Millie Lunceford.

While he was 59, she was only 21.

David and Millie’s marriage was short. After only seven months, in November 1851,

David died leaving Millie as a young widow.

That was barely enough time for them to really get to know each other. As was the trend at the time, Millie wasn’t

content to remain single. In fact,

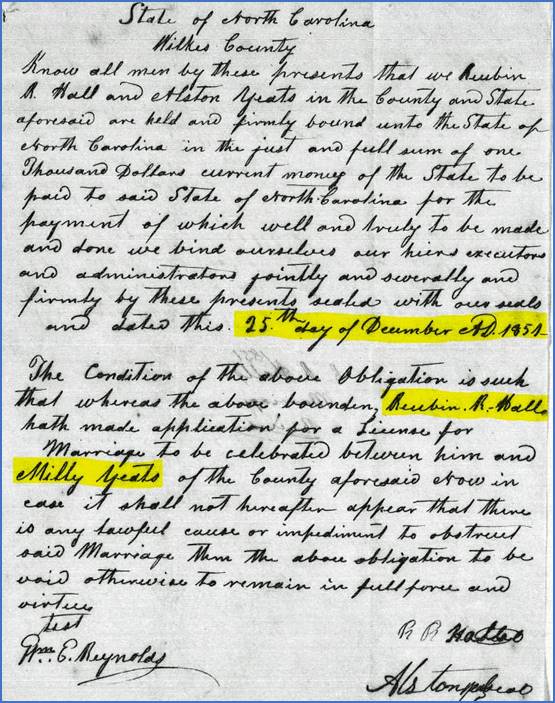

just days later on December 25, 1851, she remarried – this time to someone

her own age. Who was this young man? His name was Reuben Riley Hall. Sound familiar? By 1860 he and Millie had three

children. We’ll get back to Riley

shortly.

1851 Marriage of Reuben

Riley Hall and Milly Lunceford Yates Meanwhile, Letha Yates Bauguess was

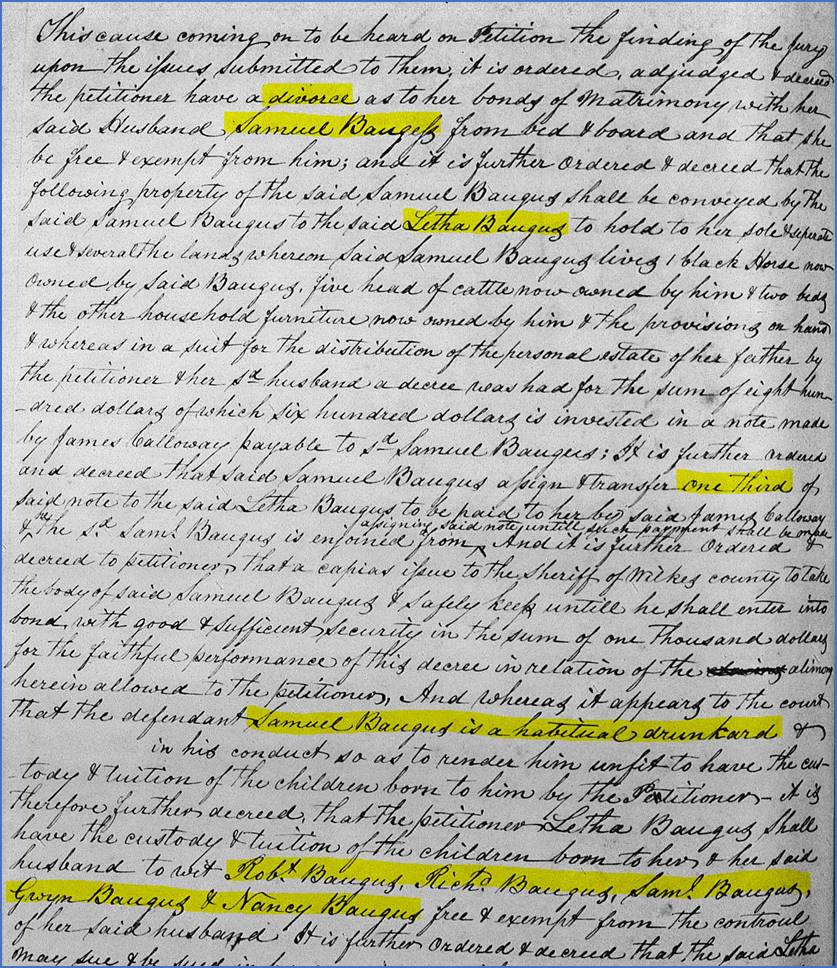

having problems with her marriage. In

September 1854 she filed for divorce from her husband Samuel. The court record says he was a “drunkard”

who was unfit to care for his five children.

Divorce was not particularly common in the 1800s, so perhaps that’s an

indication of how bad their relationship had become. They were due to receive $800 from the

settlement of her father’s estate, but due to the divorce, they would need to

split that inheritance. Letha would

only get one third of it. That doesn’t

seem fair at all. Samuel was the one

at fault, and Letha needed to care for her five children, with presumably a

sixth child, daughter Mary, on the way.

No, not fair at all, but such were the laws at the time.

1854 Divorce of Samuel J.

Bauguess and Letha Yates Bauguess The 1860 census census lists Letha (age

41) living with children Robert (18), Richard (15), Samuel (13), James (10),

Nancy (8), Mary V. (6), and Almeda (3).

She was listed with no real estate and personal property valued at

$150. This was certainly on the low

end of personal wealth for a household in that year, but many of her

neighbors had similar property values. Now back to Riley Hall. This is where his story becomes more

intertwined with Letha’s story, and their relationship can be quite

confusing. As mentioned earlier, Riley

was married to Letha’s stepmother Millie.

Yes, Letha was ten years older than her stepmother Millie, and Millie

had only been married to Letha’s father for seven months, but they did

technically have that relationship. It

was while Riley was married to Millie that he had a child with Letha. You can’t help but wonder what Riley must

have been thinking at the time. What

did his wife Millie think of this revelation?

What were Letha’s plans? After

all, Letha was the one who provided Riley’s name to the court. The court’s decree for Riley to support

his child was made on June 29, 1861.

Two weeks earlier on June 12, 1861, he voluntarily enlisted as a

private in the 26th NC Regiment Infantry for one year of service for the Confederacy. While this drama was playing out in their

personal lives, the country was in turmoil.

Just weeks earlier on May 20, 1861, North Carolina officially seceded

from the Union. One wonders if Riley

readily joined the war because of his strong commitment to the cause, or if

we was escaping his situation at home.

He probably had an unhappy wife at home; the mother of his child

needed financial help for her now seven children; and the state needed

soldiers for what would become a terribly tragic and bloody war. Whatever his motivations might have been,

Riley went to war.

1861 Bond: Riley R. Hall is the father of Letha

Bauguess’ child. As a private in Company C, Riley’s unit

left Wilkesboro on July 8 and arrived in Raleigh four days later. The 26th NC Reg spent the following year

east of Raleigh near the towns of New Bern and Kinston where they had

encounters with Union troops. By March

1862, muster rolls show that Riley was now signed up for three years of

service or the duration of the war.

His regiment went north to Petersburg and Richmond in the summer of

1862 where they encountered heavy fighting and suffered casualties. Riley was reported sick with rheumatism in

October and November, but he eventually returned to duty. The regiment remained in southeast Virginia

and eastern North Carolina for several more months. Understandably, Riley had had enough of

this war, and he decided to do something about it. On May 17, 1863, he was reported as a

deserter. He made his way westward

back home, being careful to avoid battles, Confederate troops, and the Home

Guard. The trip likely took a week or

even ten days since he was trying to stay hidden as he went. You can imagine the relief he must have

felt as he got closer to his Wilkes County home and into familiar territory,

but that relief would be short-lived. Officially, the Home Guard was an

outfit comprised of men who had avoided military service due to age or some

other circumstances, and they were charged with protecting the homefront

while husbands and fathers were away in the war. But more accurately, they acted as a group

of lawless thugs who served as their own judge, jury, and executioner in

cases that involved the loyalty of citizens.

Soon after Riley arrived back home, tired and hungry from a 300-mile

walk, it wasn’t his family who was there to greet him, but the Home Guard. They had likely received word to be on the

lookout for a deserter and traitor to the cause. Riley’s loyalties couldn’t be trusted and

his unacceptable actions should be dealt with accordingly. And that’s what happened. A log entry in Levi Absher’s ledger notes

that Riley Hall was shot and killed as a result of his desertion. No date was given. Riley’s wife Millie and their children

had lost a father, and Letha wouldn’t be getting any financial support from him. The war would continue for two more years,

but times would remain difficult for much longer as the South attempted to

rebuild and restabilize. The

Confederate dollar had become worthless, and families who had little suddenly

had even less. The 1870 census lists Letha Bauguess,

age 50, working as a housekeeper while living with another family. None of her children were living with

her. While her four sons would have

been in their 20s, her three younger daughters were teenagers at the

time. Her daughter Nancy had married

in 1868 and was living in neighboring Alexander County. Perhaps daughter Mary was also there since

she is found in Alexander County records a few years later. No other record of daughter Almeda has been

found after the 1860 census when she was three years old. Letha continued to board with

neighborhood families until her death on January 24, 1910, in Rock Creek in

the same community where she was born.

She was 90 years old. Riley’s widow Millie is found in the

1870, 1880, and 1900 censuses living with her children and

grandchildren. Riley had died during

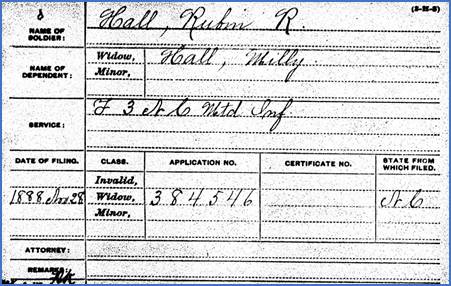

the war. Hadn’t he? There’s a Civil War pension card on file

for Milly Hall, widow of Rubin R. Hall.

The request was filed from North Carolina and dated November 28, 1888. It says “Rubin” served in the 3rd NC

Mounted Infantry ... for the Union Army!

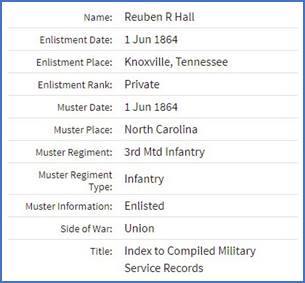

Another index lists the same Reuben R. Hall who enlisted in this

regiment on June 1, 1864, in Knoxville, TN.

Two documents for Reuben R.

Hall in the 3rd NC Mounted Infantry Could this be the same man? Could he have escaped from the Home Guard

and joined the Union Army the following year?

It seems like a stretch, but the name matches our Riley Reuben Hall in

Wilkes County. His wife is listed as

Milly, and the dates would work out to explain that he joined the Union Army

after deserting the Confederacy. This

mounted infantry patrolled northwestern North Carolina in an area that included

Wilkes County. I checked but wasn’t

able to find another man by this name who lived in North Carolina or

Tennessee. I wasn’t able to find the full

pension request made by this Milly Hall in 1888 which might provide more

details to determine if this was the same man. It might simply be a coincidence, but it’s

certainly worth exploring.

Comment below or send an email - jason@webjmd.com |