Blog

Article List Home My Research Services Contact Me

|

Surry: Revolutionary War, Elihu Ayers, Iron Works,

Elkin October 1, 2021 The Adventures of Elihu

Ayers If you want to hear stories about the

life of a volunteer soldier who lived in Elkin during the Revolutionary War,

you won’t find a better source than Elihu Ayers, and fortunately, he

documented some of those stories. He

didn’t live in Elkin long – only from 1777 until 1791 – but he had a lot of

experiences during those 14 years that are of local and national interest. Of particular interest to me is the fact

that he stayed at and guarded the David Allen Iron Works in between trips to

hunt down Tories in the surrounding area.

For over two years, I’ve been

researching the old Iron Works with other history enthusiasts including Bill

Blackley, Doug Mitchell, and Gabe Mitchell.

We’ve determined that it was located on the Big Elkin Creek behind the

library on land that would later become the Richard Gwyn cotton mill and the

old Chatham Manufacturing plant. The

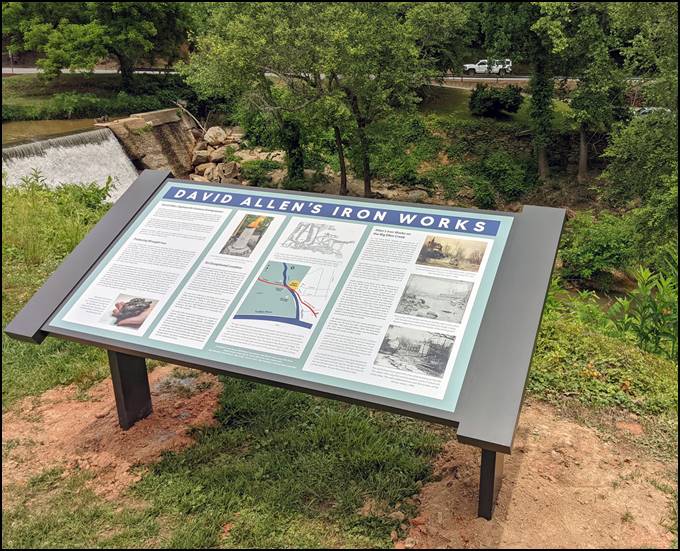

marker below was erected this summer on the bank overlooking the site to

explain what the iron works was and how important it was to the community and

to the Revolutionary War effort.

The historical marker for

David Allen’s Iron Works was installed in the summer of 2021. I have much more information on David Allen's Iron Works online

(www.webjmd.com/elkin). Until now, we had found a scattering of

references to the iron works, but nothing in the words of someone who

actually lived there. We’re lucky that

our good friend Elihu Ayers provided us with his perspective of the iron

works when he reported on his military experience when applying for his

Revolutionary War pension in 1832 and 1833.

His accounts suggest that the David Allen Iron Works was even more

significant than we first thought. Elihu stated that he volunteered as a

private under Capt. Micajah Lewis of the Wilkes Militia in January 1778 in a

regiment commanded by Col. Benjamin Cleveland when he was either 17 or 18

years old. He said that “he was stationed

at David Allen’s iron works in the county of Surry, North Carolina, to guard

them and protect the surrounding neighborhood from the deprecation of the

tories who much abounded in that section of the country and (he) was

frequently sent off in search of tories, outliers, and robbers, and would

again return to the iron works, that place being the headquarters of the

company called the Iron Works Company.” The fact that the iron works needed to

be guarded and protected shows how turbulent, uncertain, and perilous daily

life was during the war, but it also illustrates how important the iron works

must have been to be worthy of being guarded.

Valuable and limited resources (soldiers and weapons) were used to

ensure that the production of iron ore could continue uninterrupted to

provide material that was vital for the manufacturing of tools, building materials,

and weapons that would support the war effort. Elihu said that the iron works was the

local headquarters of the militia, being known as the Iron Works

Company. It’s amazing to think that a

key manufacturing operation and militia headquarters for the Revolutionary

War was located on the Big Elkin Creek in what would eventually become the

town of Elkin! Many Expeditions Elihu Ayers was born about 1760 in

Pittsylvania County, Virginia. His

father had sent him to Surry County to buy a tract of land, or since he was

only a teenager, perhaps he was tasked with claiming land that his father

Thomas Ayers had already purchased.

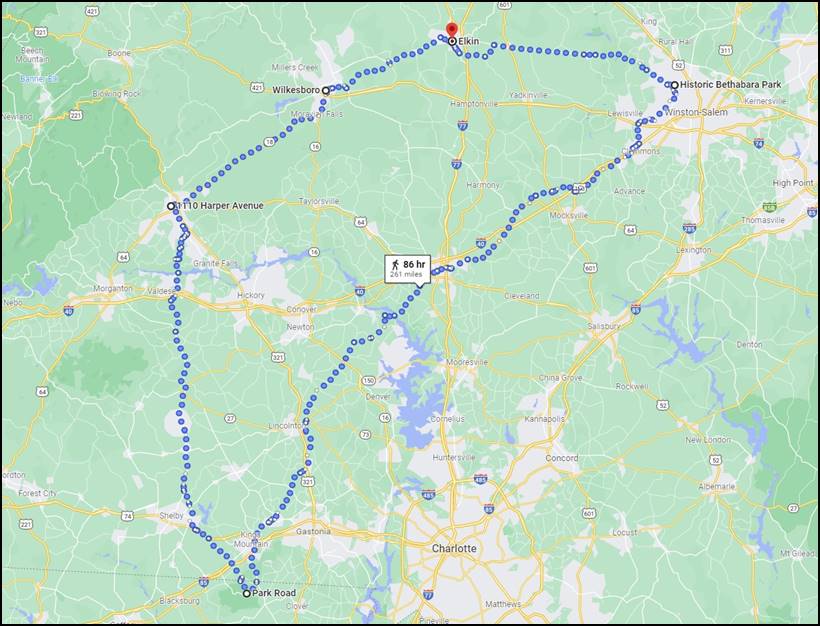

While making the 100-mile journey in 1777, I wonder if Elihu had any

idea that he would soon be serving as a soldier.

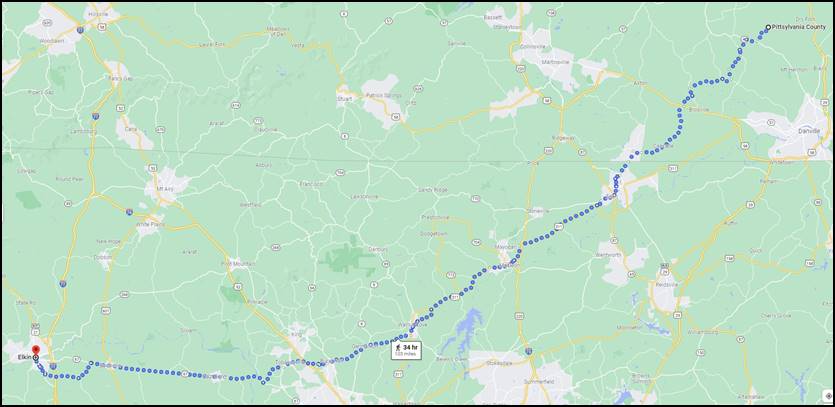

Elihu Ayers traveled 100

miles southwest from his home in Pittsylvania County, Virginia, to the Iron Works on the

Big Elkin Creek in Surry County, North Carolina. (click to

enlarge) While the iron works served as Elihu

Ayers’ home base, he spent much of his time away from the headquarters as he

was tasked with hunting for Tories or participating in battles. One of his first missions was to search for

a Tory captain named Richard Murphey “who was doing mischief in the

country”. He was part of a small group

who spent 26 days pursuing him on Mitchells River, Fishers River, and Codies

Creek. Soon after, he went in search of Tories

William Kail/Koyle and Samuel Jarvis whom they apprehended “near the Swan

Ponds in Surry County”. This is now

Swan Creek near Wilkes and Yadkin county line. Elihu stated that this capture resulted in

a court martial and a hanging of the two men.

Well, actually two and a half men.

On that same day, he was present for the “half hanging” of William

Combs whom they let off on the promise of better behavior. I wonder if the other two men also had the

opportunity to promise to be good from now on. Later in 1778, Elihu was again put into

action under the command of Capt. Hardin to search for the Tories who had

robbed the home of Capt. Daniel Carlan at the foot of Flower Gap in

Virginia. This appears to be north of

Cana near Fancy Gap. The chase led

west through the mountains to the Little River, then to the Three Forks of

New River (perhaps near Boone, NC), then to the Ball Mountain (perhaps near

Burnsville near the Tennessee border).

They were unable to catch their quarry, so they were “marched back

again to their garrison at the iron works after a march of about twenty

days.”

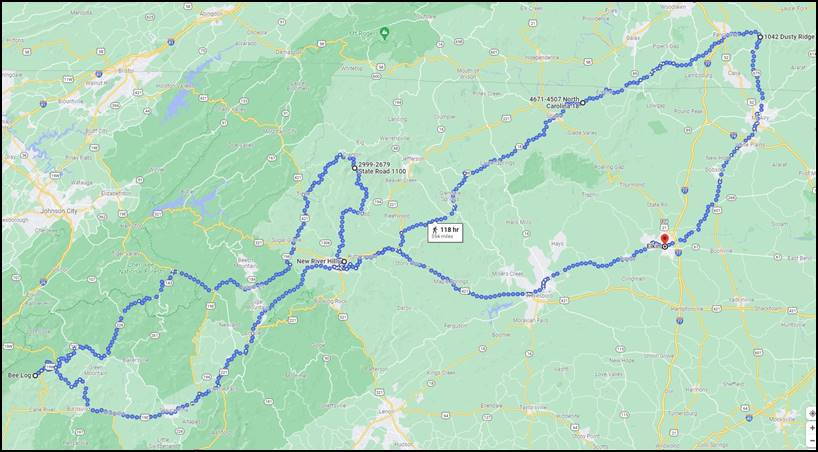

The 1778 search for Tories

took Elihu Ayers on a search throughout western North Carolina that covered more than 350

miles in twenty days. (click to

enlarge) Late in 1778 he was marched under Capt.

(Micajah?) Lewis in search of Col. Briant of the Tories. They went to Burke courthouse (Morganton),

then east to Salisbury, north to the Shallow Ford of the Yadkin (near Hwy

421), and finally back to the iron works.

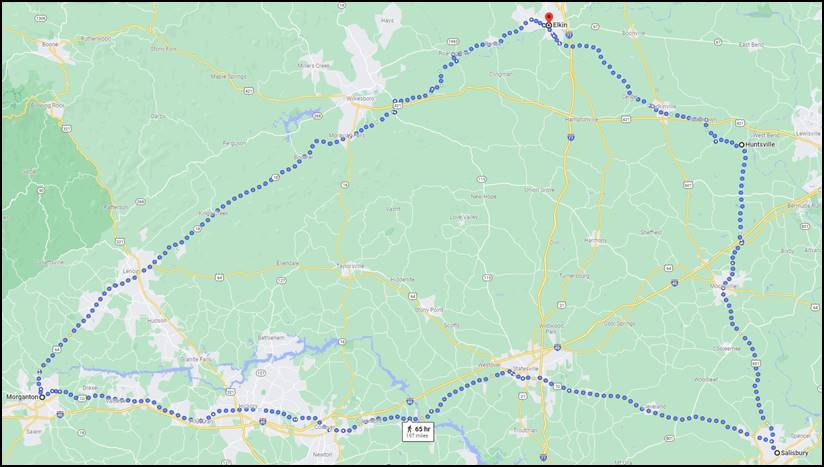

The 1778 search for Col.

Briant was a 200-mile trip that lasted about six weeks. (click to

enlarge) Elihu Ayers said he was discharged on

February 10, 1779 after he requested that he be allowed to return to

Pittsylvania County to get his father who had sent him a letter saying he

wished to move to his new land in Surry County. He returned home, and in early 1780 after

being away for one year, he was back in Surry County. On April 5, 1780, he again entered service,

this time under Capt. Salathiel Martin of the Surry Militia. He was appointed Orderly Sergeant, and he

“remained guarding the iron works some length of time”. Before Elihu could get too accustomed

to the smell of burning charcoal and the sound of crushing stones at the iron

works, it was time to go on another mission.

He was marched under Capt. Martin to the Shallow Ford of the Yadkin

River where they had an engagement with the Tories. Capt. Martin was briefly taken prisoner,

but was recovered the next day. They

returned to the iron works. In August 1780, he was marched under

Capt. Martin from the iron works to Wilkes courthouse where they joined

several other companies under Col. Cleveland.

This was the beginning of the march to Kings Mountain. They stayed in Wilkes for three weeks as

more companies gathered. During that

time they participated in “sham fights” where half of the troops pretended to

be the enemy, serving as practice drills for the men and the officers. They then went to Criders Old Fort (now

Lenoir). Elihu estimated that the army

consisted of several hundred men when they marched south to Kings Mountain. As Elihu succinctly put it, “They ascended

the mountain, attacked the enemy.” He

said he saw Ferguson lying wounded when Col. Campbell ordered him to

surrender. Elihu said Ferguson replied

that “he was on Kings Hill, and he meant to die in the king’s cause.” Elihu Ayers wasn’t one to mince words when

he described what happened next. He

said that upon hearing Ferguson’s defiance, “Campbell immediately hewed him

to pieces and left him dead on the mountain.”

After the battle, Elihu guarded the prisoners and assisted in marching

them to Bethabara, the old Moravian town.

Elihu’s march to Kings

Mountain and back in 1780 was over 260 miles.

(click

to enlarge) After only eleven days of idle time at

home, Elihu was again called upon to guard the iron works under Major Herndon

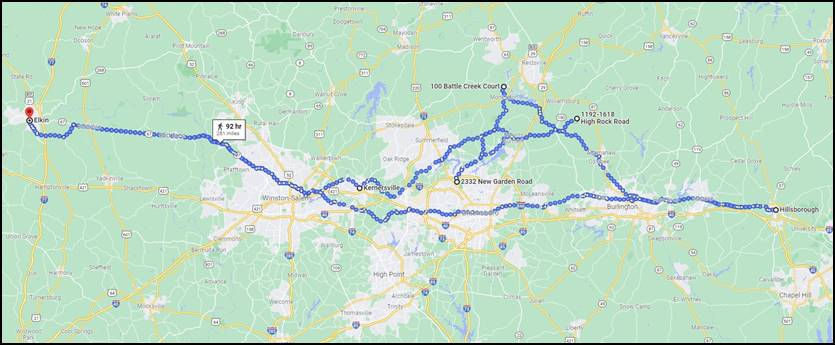

in a company commanded by Capt. Richard Allen from Wilkes County. In February 1781, he marched under Capt.

Allen to Dobson Crossroads (now Kernersville), then to the High Rock Ford on

the Haw River (south of Reidsville).

They were in search of British Gen. Cornwallis who was thought to be

in the area. The Battle of Guilford Courthouse, or

simply “The Battle of Guilford” as Elihu referred to it, occurred on March

15, 1781. He said that during the

first or second round, the North Carolina militia “got panic struck, himself

amongst the rest, and ran from the scene of action.” They didn’t stop until they reached the

Troublesome old iron works which was 9 or 10 miles away. Not to be confused with the iron works on

the Big Elkin, the Troublesome Iron Works was on Troublesome Creek south of

Reidsville and at least 13 miles northeast of the Guilford Courthouse

National Military Park. The day after their escape from the

battle, Elihu and the others rejoined Gen. Green and marched with him in

continued pursuit of Cornwallis. While

near Hillsborough on April 7, 1781, they were discharged by Gen. Green. Elihu returned home and was not called back

into service, and the Iron Works Company had nothing more to do.

Elihu’s march to Guilford

Courthouse and Hillsborough in March and April 1781 was more than 281 miles. After the war, Elihu Ayers married

Lydia Owens in 1786 either in Surry Co, NC, or Halifax Co, NC. They had several children. In his pension declaration, he said that he

remained a citizen of Surry County until 1791 when he moved to Patrick Co,

VA, where he had lived ever since. He

gave his first report of his military experience on November 16, 1832. Perhaps that account didn’t have enough

detail to satisfy the government officials, so he gave a more in depth

account on October 29, 1833, which resulted in him getting a pension which he

received until his death in 1844. Elihu Ayers provided more information

in his pension declarations than many others did at that time. We’re lucky to have his accounts since he

was a witness to so many critical events during that chaotic time in our

nation’s history. I’ve transcribed

both of his pension declarations, and they can be read

in full here.

Comment below or send an email - jason@webjmd.com |