Blog

Article List Home My Research Services Contact Me

|

Wilkes March 17, 2022 Battle of the Roundabout I’ve always heard that Benjamin

Cleveland lost his Roundabout Plantation because someone else had a better

title to that land. I later learned

that William Terril Lewis was the one who had that better title, but

why? How was Lewis’ claim to the land

better than Cleveland’s? Now I know.

(I’m not sure about the authenticity of

these images, but they were online. We’ll

use them to visualize our challengers.) Benjamin Cleveland was one of the area’s

most colorful characters during the Revolutionary War. He was the Colonel over the Wilkes County

Regiment and fought in the pivotal Battle of Kings Mountain. He was powerful, persuasive, and stubborn. He was accustomed to getting his way. He is famously known for rounding up

British-sympathizing Tories and hanging them from the eponymous Tory Oak that

stood beside the Wilkes courthouse. He

earned the nickname “Terror of the Tories” for his unrelenting treatment of

marauders and looters. Beginning at Wilkes

County’s formation in 1777, he held several high-level government posts that

provided him the authority to make sure the county was governed in a way that

he saw fit. Much could be written about the

specific adventures of Benjamin Cleveland, but the point is that few who

challenged him were successful. He was

instrumental in building and developing the new county, and sometimes that

required strong-hand tactics that weren’t always appreciated by others. As for William Terril Lewis, he seems

to have been equally influential in neighboring Surry County. He owned thousands of acres along the

Yadkin River throughout Surry County and at least as far west as Wilkesboro. This battle for the title to Roundabout was

also a Battle of the Titans. Cleveland

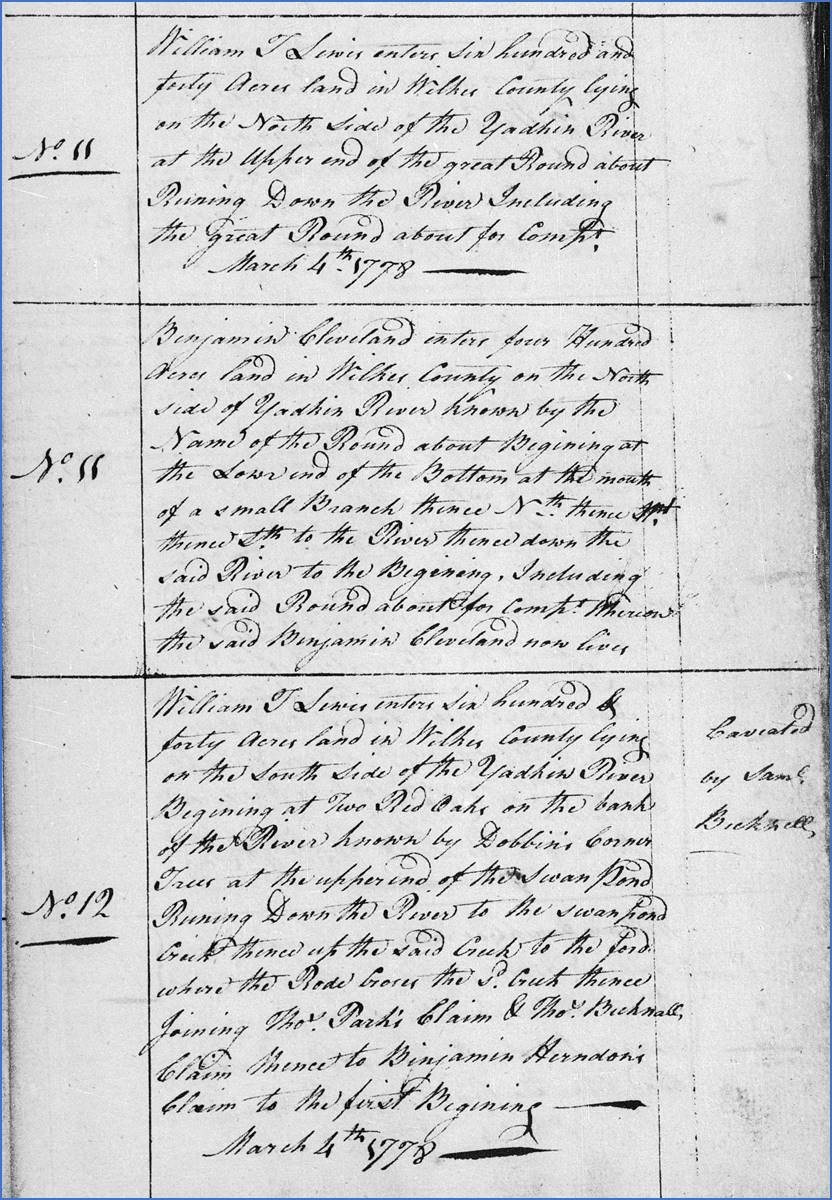

and Lewis were among the wealthiest landowners in the area. North Carolina’s new land entry office opened

in early 1778, and on March 4th several entries, or petitions for

land, were made in Wilkes County including an entry by Benjamin Cleveland for

400 acres “on the north side of the Yadkin River known by the name of the

Roundabout”. Today this is along Hwy

268 in Ronda.

Notice that Entry #11 was the one to

Benjamin Cleveland. Immediately before

it, another Entry #11 was issued to William T. Lewis. It was similarly described as 640 acres “on

the north side of the Yadkin River ... including the great Roundabout”. How can two people be claiming the same Roundabout

land? They can’t both own it, and that’s

the problem.

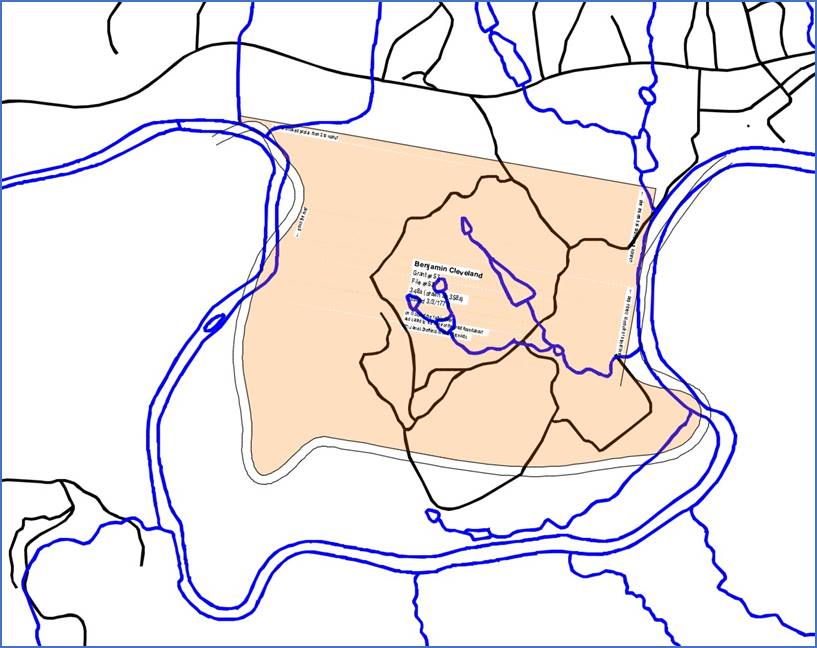

Notice that the metes and bounds that

form the Roundabout tract (shown above) are much smaller than the actual land

enclosed by the Yadkin River. I wonder

if Cleveland might have had his foot on the scale when the property was being

surveyed. If he paid the state for 348

acres when the land actually measured closer to 550 acres, he would make an

immediate profit just by submitting the paperwork. Jumping ahead to the end of the story,

it was about 1786 when the final court battle determined that Benjamin

Cleveland’s claim to Roundabout was inferior and he was forced to give it up. Even though he had acquired more than 3,000

acres in other parts of the county, Cleveland moved south to Oconee County,

SC. Maybe he found a good deal on land

there that he didn’t want to pass up.

Or, maybe he was angry about losing Roundabout, and he wanted to get

away from the “thieves” who stole his homeplace. Either way, he lived in South Carolina

until his death in 1806. And now, the rest of the story... What made it evident to the court that William

Terril Lewis had a better claim to the land?

They both entered the same land on the same day, and Cleveland’s entry

resulted in the land grant. I found the

answer in a book by A. B. Pruitt

titled “Petitions For Grant Suspensions (Part 2)”. As it turns out, Lewis had evidence of a

much earlier deed to the property. On 9/23/1778, just six months after the

land was initially entered, William T. Lewis attended the district Superior

Court to state his case. He said that “sometime”

ago he bought two tracts from Hugh Dobbins in Wilkes County on the Yadkin

River. One was the Roundabout tract,

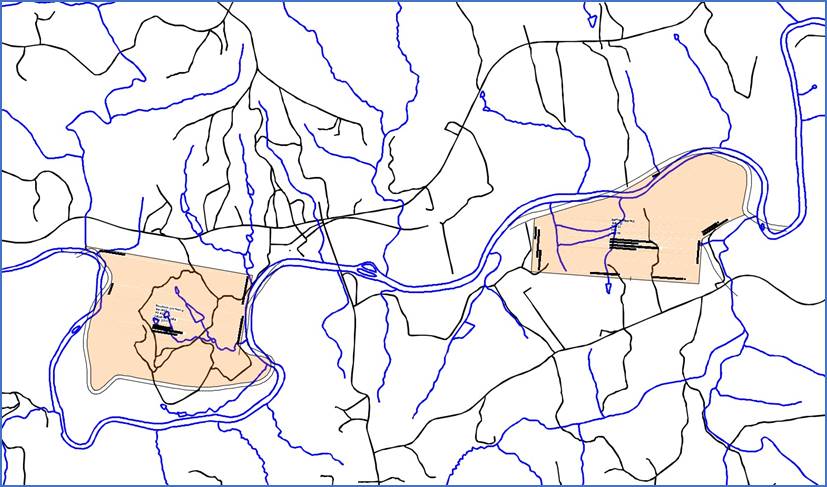

and the other was the Swan Pond tract.

Notice on the entry book page shown above that Entry #12 is to William

T. Lewis for 640 acres on the Swan Pond.

A note in the margin says, “caveated by Sam’l Becknell”. This meant that Samuel Becknell objected to

Lewis’ entry because he had been granted the Swan Pond tract just as Cleveland

had been granted Roundabout. Now Lewis

was telling the court that the state had wrongly granted land to Cleveland

and Becknell and that he was the rightful owner of both tracts.

The Swan Pond tract was on the south side

of the Yadkin River about a mile and a half east of Roundabout, at the mouth

of what we now call Swan Creek. Arguing before the court, Lewis stated

that he fairly purchased the land from Hugh Dobbins who had purchased it from

Earl Granville’s Land Office. While

Lewis didn’t provide dates, Dobbins would likely have bought these two tracts

in the 1750s or early 1760s before Granville’s Land Office ceased

operations. Lewis told the court that

he heard that he would likely lose the caveat trial. He said his opponents claimed that Dobbins’

warrants and surveys were counterfeit.

To prove his case and support his claims that the documents were legitimate,

he sought the testimony of Gen. Rutherford who had been the Deputy Surveyor

for Granville’s office. He also sent

for Thomas Frohock, a representative of John Frohock (deceased), who was Granville’s

entry taker and surveyor. Lewis presented

a certified receipt showing that Dobbins had paid the entry fees, but the

jury was unconvinced. They found in

favor of Cleveland and Bicknell. Lewis “violently” suspected that the

jury was “willfully partial” to Cleveland, but he wasn’t able to provide

proof. At some point, Lewis and his

attorneys requested a new trial on the basis that the county court decision

was biased against him. During that

county trial, Cleveland’s attorneys repeatedly interrupted his own attorneys

as they explained that none of the original jurors were freeholders which was

required. Secondly, their verdict was contrary to

similar cases with similar evidence. Thirdly,

his witnesses Rutherford and Frohock were prevented from testifying, and

their original evidence of the Dobbins grant wasn’t allowed. One of Lewis’ attorneys said that he overheard

Cleveland talking with one of the justices who had decided the case, telling

him, “you behaved like a soldier”. William T. Lewis must have continued to

press the matter, eventually receiving a future court date to retry the case. In 1785, a Wilkes deed (Bk A1, p450)

between Cleveland and Joel Lewis (probably William’s brother) mentions the

pending case in the Superior Court of Law and Equity in the District of

Morgan. While Lewis won the case

against Cleveland for the Roundabout tract, it appears that he lost his case

against Becknell for the Swan Pond tract. I searched online for a record of the

Granville Grants to Henry Dobbins, but I didn’t find anything. I also searched the Rowan, Anson, and Surry

County deed books for the transaction between Dobbins and Lewis, but I didn’t

find anything there, either. It would

be nice to see the proof that Lewis presented to the court. Perhaps these documents are among the

records that have been lost to time over the past 240 years. Or another possibility is that Cleveland was

right: Lewis’s documents were counterfeit. That would mean Hugh Dobbins never officially

owned the two tracts and, therefore, he couldn’t have sold them to Lewis. We might never know the legitimacy of Lewis’

claim, but it worked. And now we know

how Benjamin Cleveland lost his Roundabout estate.

Comment below or send an email - jason@webjmd.com |