Blog

Article List††††††††††† Home†††††††† My Research Services††††††††† Contact Me

|

Wilkes May 21, 2022 Ezra Deborde, Reluctant Soldier He had no interest in fighting someone

elseís war.† However, as an able-bodied

farmer in the hills of Wilkes County, the local Home Guard was tasked with making

sure that everyone who could serve, did serve.† That included Ezra Deborde.† In 1863, the Civil War was fully under

way, and most men were away from their homes in Traphill at the foot of the

Blue Ridge Mountains.† Ezra was a 38-year-old

husband and father of seven young children.†

He had a modest farm within a couple miles of Stone Mountain, and he

needed to be home to run that farm.†

Why should he risk his life in battle so that wealthy landowners could

maintain the right to own slaves who ran their plantations for them?† No, he had nothing to gain by going to war,

and that was a popular sentiment among many of his neighbors.

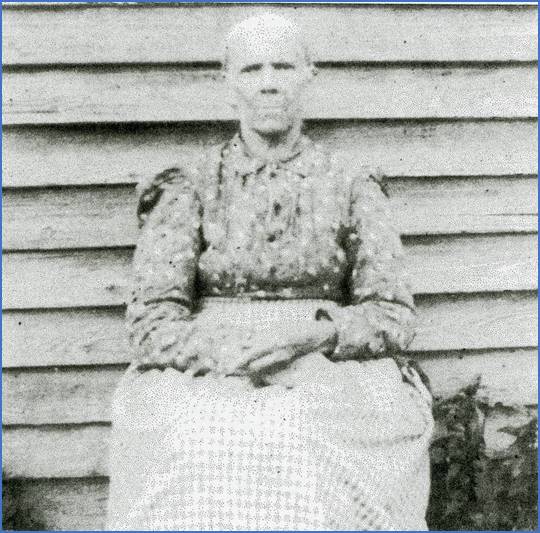

Mary C. Boaz Deborde

(1828-1913), wife of Ezra Deborde. In 1862, the Confederate Congress

passed a conscription law that all men between age 18 and 35 could be

drafted.† A major exception was that

anyone who owned more than 20 slaves was exempt.† And if someone was wealthy enough, he could

pay someone else to serve as his substitute.†

Many saw this as justification for calling it ďa rich manís war and a

poor manís fight.Ē At 38 years old, Ezra was slightly outside

of the draft age.† But the Home Guard

often made up the rules as they saw fit, and they felt that he should join

the local regiment.† Knowing this, Ezra

decided to go into hiding with the hope that the war would soon end and he

could soon rejoin his family.† He knew

of a small cave formed by an outcrop of rocks on a hillside where he could

hide.† The entrance could be disguised

by covering it with brush.† If someone

didnít know where it was, they wouldnít see it.† Most of his time would be spent just outside

the cave where it was more comfortable.†

When he heard someone coming, he would get inside.† He could get water at the creek just a

hundred yards down the hill.† As for

food, one of his children would occasionally bring him meals, being careful

that they werenít followed.† Sometimes

the family dog would join his son or daughter as a companion on the trip. Below are photos of three of Ezraís

children.

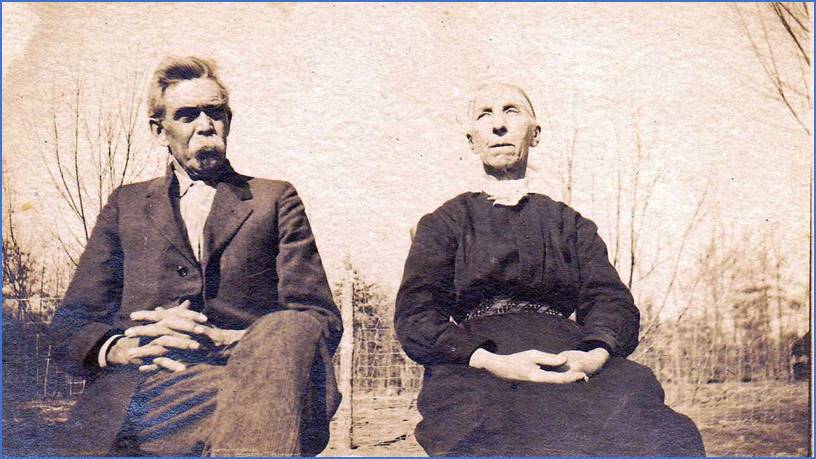

Ezraís son William Reid

Deborde (1852-1944) with his wife Cidney Jane.

Ezraís daughter Sarah Deborde

Brooks (1853-1935).

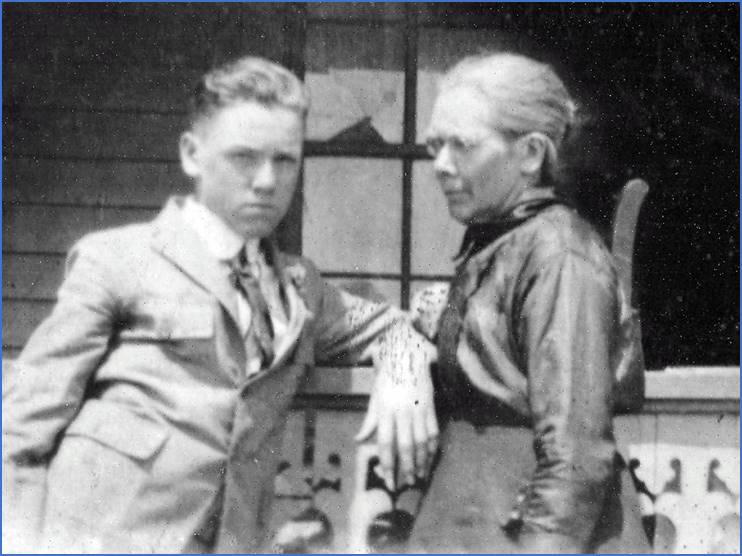

Ezraís daughter Mollie

Deborde Byrd (1861-1923) with her son Ray. His hiding arrangement worked well for

a while, but the Home Guard had never given up on recruiting Ezra.† They had been keeping an eye on his home,

waiting for him to make an appearance.†

He never showed up, but they knew he was nearby despite his family

claiming that they didnít know where he was.†

Whether it was a devised plan by the Home Guard or simply a

coincidence, Ezraís hiding spot was given up by the family dog.† One day when Ezraís dog meandered into the

woods, the men followed, and it led them directly to his hiding place.† Ezraís attempts at avoiding the fight had

come to an end. Years later, his widow Mary said that

her husband left home on October 9, 1863.†

Ezra Deborde mustered into the Confederate Army in Co. G, 58th

NC Reg on October 25 at Camp Holmes in Raleigh.† The major battles of Gettysburg and

Vicksburg had ended only three months earlier, and news of those devastating

events had traveled far.† It would be

understandable if Ezraís throat was dry and he had a sick feeling in his

stomach when he was standing before the officers to enlist.† Thereís no doubt that a member of the Home

Guard was by his side to make sure he didnít run away. During his first days as a soldier, he

wrote letters back home.† The last

letter his family received from him was dated November 9.† His regiment had suffered significant

casualties in recent battles in western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee,

and thatís where Ezra met up with them.†

Perhaps his first battle experience was the Battle of Missionary Ridge

near Chattanooga on November 25.†

Unfortunately, this would also be his last battle.† Over two days, the Confederacy lost over 6,500

men including Ezra Deborde.

ďBattle of Missionary RidgeĒ

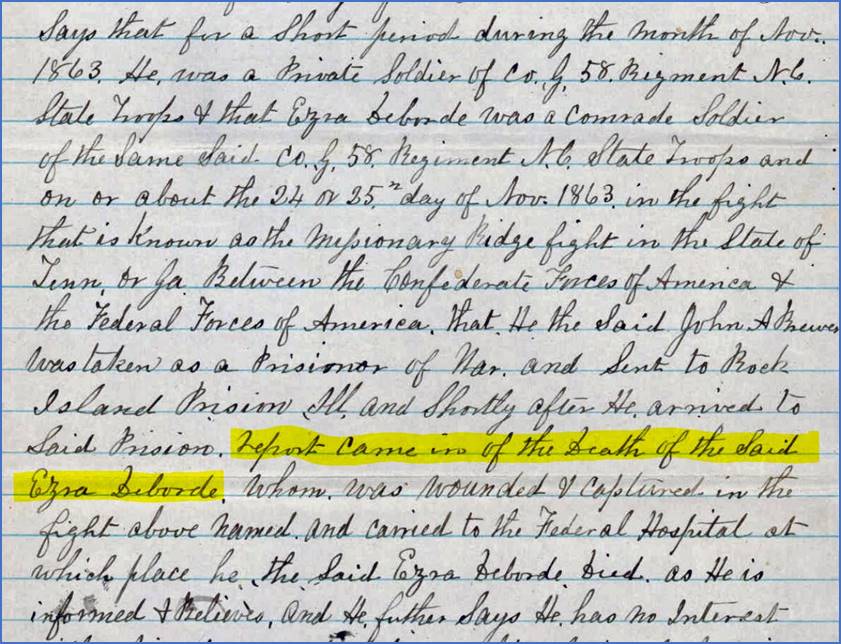

by Kurz and Allison, Library of Congress In 1885, Ezraís widow Mary applied for

her husbandís military pension.† In an

affidavit by John A. Brewer, he stated that he served with Ezra at the Battle

of Missionary Ridge.† John was taken

prisoner and sent to Rock Island Prison in Illinois.† Shortly after arriving there, he received word

that Ezra Deborde had been wounded and captured in the battle.† He said that Ezra was taken to a Union

hospital where he died.† An affidavit

by George W. Brown included similar details.†

He, too, was taken prisoner.†

After asking about Ezra, he learned that he had been seriously wounded

and died shortly thereafter.

Portion of the affidavit provided

by John A. Brewer in 1885. It's a sad end to a sad story.† For every Civil War story of heroism,

triumph, and victory, thereís an equally emotional story of tragedy and defeat.† Itís important to remember that both the

good and the bad are part of our history. Iím not directly related to Ezra Deborde,

but he was a neighbor to many of my ancestors.† This information is mostly from records at

the NC Archives, with additional details from stories Iíve heard and read

from his descendants.

Comment below or send an email - † jason@webjmd.com |