Blog

Article List Home My Research Services Contact Me

|

Wilkes November 7, 2022 The Legal Troubles of

Robert Bauguess It’s December 6, 1849, and a crowd has

gathered in front of the steps of the courthouse in Wilkesboro, North

Carolina. Many are here to take part

in a land auction that’s set to start within the hour. Others are here to watch the event. One man hopes to stop the auction from

taking place at all. His name is

Robert Bauguess. He’s 72 years old,

and he’s trying to reason with James Gwyn, the man in charge of the

sale. Robert explains to Mr. Gwyn that

the land he is about to sell did not technically belong to the late Charles

Harris. It’s his own land, the land

where he has made his home for more than thirty years. His pleading falls on deaf ears as the

auction begins. Robert Bauguess didn’t come to the

auction alone. He has nine children

who live nearby, and two of his sons came with him. If he’s lucky, one of his sons will be the

high bidder, allowing him to keep the 200-acre tract where he lives. But he knows that’s a long shot. Not only could someone else outbid them,

but he doesn’t have complete confidence that his sons are dedicated to the

cause. After all, if they wanted to

make sure the land stayed in the family, they could have paid what was due a

long time ago and avoided this whole thing. “We’ll start the bidding at $200! Do I hear $250?” The auction has begun. Hands start to raise as the auctioneer

calls out increasingly higher prices.

He’s encouraged when his son John is recognized with a bid of $397,

but that hope is quickly dashed when Owen Hall raises his hand with a bid of

$399. “Going once. Going twice. Sold for $399!” And that’s it. The auction is over. Robert realizes that his home now belongs

to someone else, but that’s when he makes an important decision. “I’ll take them to court.” The Legal Battle Begins Three months later, in March 1850,

Robert Bauguess and his legal counsel are standing before the Wilkes County

Court of Equity to make his case. He

can’t read and write, and he is too poor to hire his own lawyer. The court has appointed him one who has

prepared his statement. It begins by

stating that Robert was residing on the disputed tract in 1844 when he became

indebted to his son-in-law Charles Harris in the amount of $60. In return, he sold his 200-acre home tract

to Harris for $750. That was more than

enough to cover the debt, but he sold it all because he didn’t want to divide

the land.

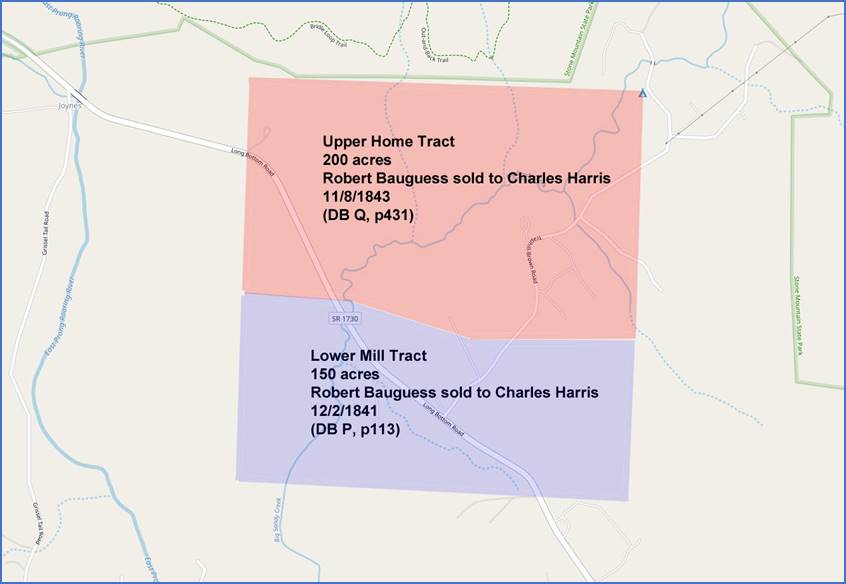

Robert

Bauguess sold his lower mill tract to Charles Harris in 1841. The

land in controversy was the upper home tract which Bauguess sold to Harris in

1843. This

is located on the south side of Stone Mountain State Park where Big Sandy

Creek crosses Longbottom Rd. It is a

half mile north of Old Roaring River Baptist Church. Robert tells the court that he and

Harris had an agreement that when he was able to repay him, Harris would sell

the land back to him. That has been a

well-known fact in the community.

Robert tells the court that both he and Harris often spoke of this

being a temporary arrangement.

Robert’s statement explains that Harris died the previous July, but

their agreement is still valid. He

should be able to pay $60 to the estate and be recognized as the owner of the

property. Robert stated that Harris left three

minor children named Joseph, Almedia, and Sarah Jane. These were his grandchildren. Since Harris didn’t leave a will, the court

had appointed James Gwyn, a county officer, as the administrator of the

estate. It was soon determined that

Harris was in debt when he died, and his personal property is insufficient to

pay those debts. James Gwyn has sold

this 200-acre tract to settle the estate.

Robert says that Gwyn knew about his agreement with Harris, and that

he shouldn’t have carried out the sale.

He says that the winning bidders – Owen Hall and his partner Thomas

Casey – also knew. He had made this

point very clear to them on the day of the sale! He even tried to give Hall and Casey the

$60 that he owed on the land, but they refused the offer. Now they’re attempting to forcibly remove

him from the only land that he owns.

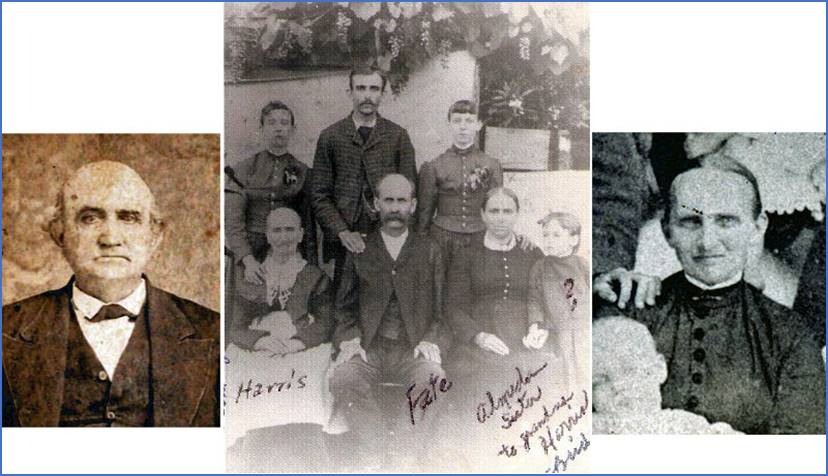

Family

of Charles Harris (1801-1849) Left

photo: Son Joseph Harris (b1842) Center

photo: Wife Fannie Bauguess Harris

(1818-1891) on left, daughter Almeda Harris McBride (b1846) on right Right

photo: Sarah Jane Harris McBride (b1848) Robert’s lawyers state that the court

should determine if the 1843 deed was a simple transaction or if there was an

agreement that would allow Robert to pay off his mortgage and reclaim the

land. They ask the court to find the

sale to be void and that Robert be declared the rightful owner. The Rebuttal of Hall and Casey There are two sides to every argument,

and Owen Hall and Thomas Casey have a few things to say about this. As the winning bidders, they are defendants

in the case. Their position is

simple: Robert Bauguess sold the 200

acres to Charles Harris in 1843 by way of the sheriff’s auction in

Wilkesboro. When Harris died, it

became part of his estate. The

court-appointed executor James Gwyn sold the land at auction as part of the

settlement, and they offered the winning bid.

Robert has no claim to the land, and he should step aside so that they

can take ownership. The only reason he

has been able to live on the land for the past seven years is because of the

benevolent feelings that Harris had toward his elderly father-in-law. The Witnesses Testify It’s December 20, 1850, and is now

before the justices. Multiple

witnesses will be called over the next two days by both sides. Their testimonies not only provide evidence

in this case, but they also tell us about the people who live in the

community. First up is Henry Greenwell. He says he had a mail route as a contractor

for Charles Harris who was the local postmaster. One day he went to Harris to collect his

money, but Harris said he didn’t have it.

He said what little money he did have, he let Robert Bauguess have in

return for a lien on his land. Henry’s

response was, “OK, so that means you get his land, right?” Harris replied that, no, he didn’t want the

land because he wouldn’t be able to work it.

All he wanted was his money back from Bauguess. The next witness is 50-year-old Thomas

Bryan, a prominent and respected member of the community who also happens

to be a son-in-law of Robert Bauguess, having married his daughter Nancy in

1818. He testifies that he was present

in 1843 when the sheriff sold Robert Bauguess’ land to Charles Harris. In fact, he was planning to bid on the

land, himself. But Charles Harris

asked him not to because he and Bauguess had an understanding that would

guarantee that Harris won the bidding.

Harris would run the bidding up as high as necessary, but Bauguess

would only take the $60 he needed to pay off his debt.

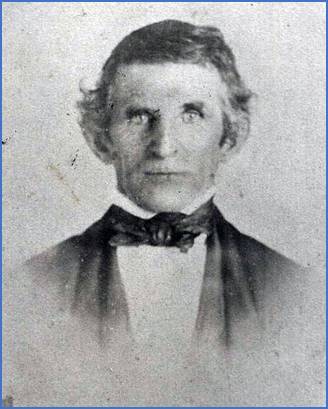

Thomas

Bryan (1800-1862), son-in-law of Robert Bauguess Bryan says that he talked to Harris a

short time before he died. This was

after Harris had gotten sick, but he was still able to walk from his home to

Gwyn and Hickerson’s store in Wilkesboro where he was employed as a

clerk. (We know that Harris spent time

in Wilkesboro in the weeks before he died.

Perhaps he was there for medical attention and was being treated by

Dr. James Calloway for his incessant coughing and chest pains.) Bryan continues his testimony by saying

that Harris said he wished Bauguess would come and redeem his land. He had paid out money for Bauguess, and now

– six years later – he wanted it back.

Harris said that if any of the Bauguess boys (i.e. the sons of Robert

Bauguess) would pay him the money, he would let them have it. He knew they had enough money to do

so. Son John K. Bauguess had offered

to buy part of it, but Harris had promised the old man Bauguess that he would

keep the land all together. Harris

said he had promised Bauguess that he could live on the land during his

lifetime whether he paid the money back or not. The next witness is 48-year-old Nancy

Bauguess Bryan, who was Robert’s daughter and the wife of the previous

witness Thomas Bryan. She says that

Harris asked her three years ago, about 1847, if her father and the boys had

plans to pay him back. She says that she

didn’t know what their plans were.

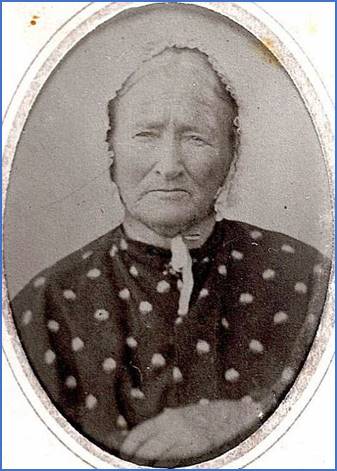

Nancy

Bauguess Bryan (1802-1885), daughter of Robert Bauguess Nancy’s younger brother, 32-year-old John

K. Bauguess is next to testify. He

says that in February or March 1849 – about four months before Harris died –

he offered to buy part of the land, but Harris refused to divide the

property, even for one of Robert’s sons, unless Robert said it was OK. John says that he was present at the 1849

auction, and that he offered the second-highest bid of $397. The defense attorney asks him if he was

angry with Hall and Casey for bidding against him, “and did you not pronounce

them rascals or damned rascals for bidding against you, and did you not

threaten to whip Thomas Casey for bidding against you?” John replies, yes, that’s true, but only

because Casey had promised not to bid against him. Another of Robert’s sons, 29-year-old David

Bauguess, is next to take the stand.

He says that he talked to Charles Harris on July 1, 1849, just five or

six days before Harris died. Harris

asked him to get his father to make a settlement on the land because he might

not live much longer, and they might be put to some trouble after his death

if the land ownership wasn’t settled. As we watch the testimony wrap up for

the day, we’re asking ourselves a few questions. The plaintiff (Bauguess) is claiming that

he only owed Harris $60. All of the

witnesses have said that if he or his sons had paid Harris that amount, he

could have all of his land back. So

why is his son John bidding $397 at an auction for that same land? It seems like he could have bought it for

only $60 at any point over the previous five years! This suggests that Robert Bauguess might

have been taking advantage of Harris’ generosity. As long as Harris was alive, Bauguess had

the benefit of the land AND the money.

Only, now that Harris was dead, the next landowner wasn’t as

forgiving.

James

Gwyn Jr (1812-1888) was the administrator of Charles Harris’ estate. He

auctioned the 200 acres in 1849. ROUND 2: More Witnesses We’re in the room again a month later when

another group of witnesses testify on January 22, 1851 at the home of justice

John S. Johnson. Witness James

Johnson says that after his return from Orange County in the spring of

1849, he talked to Robert Bauguess.

Bauguess said that he had a lifetime right to live on the property. Witness Polly Holbrook says that

one or two summers ago, Robert Bauguess asked her to borrow money. It was when he was sick with fever. He asked to borrow $500 or $600 to redeem

his land from Charles Harris. Next to testify is 38-year-old James

Burchett who has lived on the disputed tract with his wife Sally and

their children for the past two years with permission from Robert

Bauguess. He says that Robert once

told him that he had sold the land to Charles Harris and that he “had not the

scrape of a pen for a lifetime estate in it, only by word of mouth”. He goes on to say that Bauguess said he

wasn’t afraid of being put off the land if he outlived Harris, because Fannie

would not force him to leave. Fannie

is Robert’s daughter, and the wife – now widow – of Charles Harris. When asked if he is friendly with

Robert Bauguess, James Burchett answers indirectly by saying he tries to be

friendly with everyone. When pressed

further, he admits that he and Bauguess did “have a difficulty” in the past,

and that he hasn’t been back to Bauguess’ house since. James’ wife Sally Burchett testifies

next, and she is more blunt with her opinion about Robert Bauguess. She says, “I can’t say that I’m exactly

friendly (with him), for he has acted ridiculously.” Unfortunately for us, Sally doesn’t

elaborate. But we’re starting to get

the feeling that Robert Bauguess is a stubborn old man who’s set in his

ways. He doesn’t seem to be concerned

with how his actions might affect those around him. The next witness is Anderson Wood,

a 47-year-old neighbor and farmer.

When asked about his knowledge of the land title, he says that in 1847

Bauguess said that Harris paid him $300 to cover the expenses from a lawsuit

against Bauguess regarding some negros.

In return, Bauguess let Harris have the land until he could pay him

back. This is the first we’re hearing

about this other lawsuit, and we’ll revisit this new information a little

later. Round 3: Still More Witnesses Two months later, on March 17, 1851,

we’re at the courthouse in Wilkesboro to hear three days of testimony from

more witnesses. William M.

Forrester, a 52-year-old wealthy businessman says that in 1847 he asked

Charles Harris if he could buy the land now in controversy. He replied that Forrester should go ask

Bauguess. He wouldn’t sell without

Bauguess’ approval, and Bauguess never allowed it. If the testimony up to this point has

been somewhat dry, our next witness would do his part to change that. He gives his name as John M. Brown,

and we wonder if is the 26-year-old unmarried son of Presley Brown. When asked by the defense about his

knowledge of the disputed land, he says that a short time before the death of

Dr. Harris, he was cutting a ditch on the land. Bauguess told him that he would like it

done before the spring, otherwise he would not have it done because the land

belonged to Dr. Harris. When the lawyer for the prosecution

approaches the witness, his first question is, “Are you not very drunk?” Brown replies, “If I am, the law says

prove it. I am no way drunk.” The lawyer asks, “How much have you

drunk today?” “I have not drank anything but water

this day. Set this down: I always drink what’s as much as I

please.” After a futile attempt to get

any useful information from Brown, he is dismissed. Robert’s youngest son, 23-year-old Louis

Bauguess takes the stand. He says

that about 1844 (when he was only 16), he witnessed his father pay Harris

about $111. He remembers his father

preparing to pay $124, but that Harris said Bauguess had better keep a little

of it for himself. Everyone in the courtroom sits up a bit

straighter when 63-year-old former sheriff Abner Carmichael takes the

stand. He confirms the existance of

several receipts. One is dated January

1844 in the amount of $1,667 when Robert Bauguess paid the sheriff by order

of the court. Another is from 1848

when Charles Harris paid the $4 balance owed by Bauguess. He also confirms other receipts for debts

that Charles Harris paid for Robert Bauguess including $100.59 in 1843 as a

result of a court case in favor of John Long and his wife Elizabeth. ROUND 4: Return Of The Witnesses We have to wait two years before the

next witnesses are called on March 21, 1853.

Making their second appearances in the case are sons Lewis Bauguess

and John K. Bauguess. They say they

now remember their father paying Harris on two occasions. Not only did Robert Bauguess pay Harris

$111, but he had earlier paid him $450.

This was payment for the adjoining mill tract property in return for

Harris paying the costs in the suit regarding the negros Eady and her

children. (Here’s another mention of this

prior lawsuit.) ROUND 5: The Last Witnesses It’s another two years before the

controversy is addressed again. More

witnesses are present for questioning on

March 2, 1855, at the home of John S. Johnson. However, Robert Bauguess isn’t present. His 33-year-old son Robert J. Bauguess

arrives in his place with a note stating that his father was not feeling well

enough to attend. When the hearing

begins, Mary Blackburn confirms that Robert Bauguess did ask her to

borrow money, but she refused to lend it to him. William R. Sparks and John S.

Johnson were both witnesses to an 1841 deed, and they remember Charles

Harris paying Bauguess $450 for the mill tract.

Robert

J. Bauguess (1822-1914), son of Robert Bauguess Next to testify is 33-year-old, father

of five, Granville Smoot who remembers Bauguess saying that he had been

promised a lifetime right to live on the land by Harris. The prosecution asks him if the old man was

calm or in a passion, and Smoot says, “He appeared to be in fret.” The defense asks who he was in a fret with,

and he says, “With his own family.” Did

he consider Bauguess at that time to be sane or insane? “I did not consider him insane.” Robert Bauguess was certainly upset about

something, but we’re not sure exactly what that was. Hardin Spicer takes the stand. He is the 49-year-old nephew of Robert

Bauguess who lives nearby. Spicer says

that he spoke to Harris at Harris’ house in Wilkesboro after he became sick

and a short time before his death. The

prosecution asks if Charles Harris at that time expected to die soon. Spicer answers that he did, and that Harris

wanted to make a will with him as executor.

Harris also said that he had a clear deed to all of his land. Spicer ends his testimony by stating that

he believed Harris to be an honest man, never claiming anything but his own.

Hardin

Spicer (1806-1897) talked to Charles Harris about being the executor of his

will. Harris

died before writing the will. The Verdict Is In At the August 1857 term of the North

Carolina Supreme Court held at Morganton, a verdict is finally rendered. We’ve traveled the fifty miles from

Wilkesboro in anticipation of finding out how this case will finally be

decided! It’s been nearly eight years

since the controversial auction of the 200 acres following the death of

Charles Harris. Quiet fills the

courtroom as the judge enters. Taking his seat, the judge reads the

decision, “In this cause, the parties having compromised this suit by

purchasing the interest of the plaintiff in the land described in the

proceedings and by agreeing to pay all the costs of this suit, it is

therefore ordered, adjudged, and decreed by consent of the parties Hall and

Casey, that the defendants pay all property taxable costs.” Wait, what? The parties having compromised? We’ve waited eight years, and the parties have

decided to settle this out of court?

Yes, they did. Back on November

3, 1855, Robert Bauguess sold this 200-acre tract to Owen Hall for

$1,000. We’re left to wonder exactly how

that “compromise” was reached because the court records don’t explain

it. Just when it seemed like Robert

Bauguess was about to lose his home, we find out that he somehow made $1,000 by

selling land that he had already sold once before! That’s an impressive accomplishment. Owen Hall will own this land until his

death, and in 1874 the property will be divided among his children. Robert Bauguess will spend his

remaining years living in the homes of his many children, dying in 1872 at

the age of 95. Now, About That Other Lawsuit We’re not finished yet. We still need to address an issue that came

up in several witness testimonies involving a prior court case that Robert

Bauguess lost. And as it turns out, this

wasn’t Robert’s first experience with the state Supreme Court. Anderson Wood, Abner Carmichael, and Lewis

Bauguess each mentioned a prior lawsuit involving negros. To understand when Robert Bauguess’

financial troubles started, we need to step two decades back in time to March

1832 when Patty Martin sells three negros to Elizabeth Gambill. However, it’s not that simple – it never

is! While Patty still has possession

of her slaves, her brother William Martin claims ownership of them. Elizabeth Gambill takes William Martin to

court, but surprisingly the court sides with William. With the slaves determined to be his, William

Martin sells them to Robert Bauguess. Patty

Martin dies in 1836, and Robert Bauguess is appointed as the administrator of

her estate. Robert Bauguess now has possession of

the three slaves of Patty Martin. The following year, in February 1837,

Elizabeth Gambill has married John Long.

Together they sue Robert Bauguess for possession of the slaves. Bauguess says he has posession of the

slaves as the administrator of Patty Martin’s estate and by the fact that he

bought them from William Martin. Elizabeth

claims that she bought the slaves long before any of that happened. This case is appealed at the Spring

1842 term of Iredell County Court, and it goes all the way to the North

Carolina Supreme Court. In June 1842,

the high court rules that the lower court was wrong in siding with William

Martin because he obtained the slaves through trespass. He had sold what wasn’t his to begin

with. Therefore, if the proper

judgment had been given, Robert Bauguess would never have had the opportunity

to buy the slaves from William Martin.

The three slaves should be the property of John and Elizabeth Long. The Supreme Court upholds the ruling

that was issued on March 15, 1842 by the Iredell County court. Robert Bauguess is ordered to pay $600 for

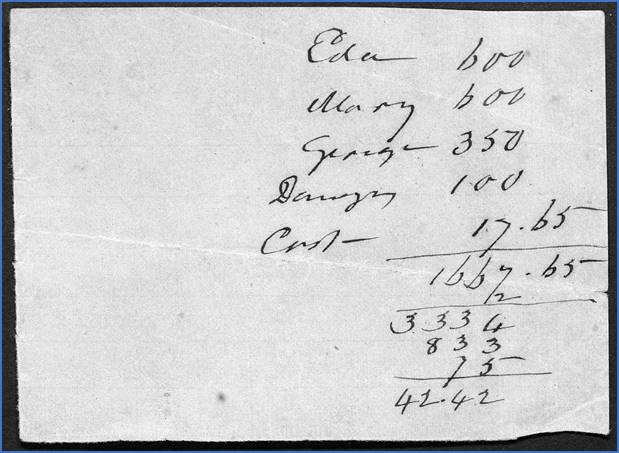

the detention of Eda/Ede, $600 for Mary, $350 for George, $100 for damages to

the plaintiff, and $17.65 in court costs.

The total fine is $1,667.65.

In

1842, Robert Bauguess owed $1,667.65 for the dentention of three slaves Robert Bauguess likely spends all the

money he has on this fine, and Charles Harris generously pays the rest. In return, Robert first sells the lower

150-acre mill tract to Charles Harris in 1841, and then the upper 200-acre

home tract to him in 1843. Charles

Harris was always extremely grateful to Robert Bauguess. When Charles and the twins Eng and Chang first

arrived from New York and decided to call Wilkes County their home in 1839, Robert

had rented them rooms in his house.

Later that year, Charles married Robert’s 21-year-old daughter Fannie,

and they lived on a tract adjoining Robert’s land. After being born in Ireland and traveling

all over the world with the twins for eight years, Charles Harris was happy

to finally settle down in a peaceful place that he could call home. He clearly felt that he could never

fully repay the favor to his father-in-law.

He was eager to offer him money whenever he needed it, with no

questions asked. But that boundless

generosity had consequences. After a

life of relative luxury without financial struggles, he was uncomfortable

with the idea of being in debt. Unfortunately

that’s the way he spent his last six years. Almost every witness who testified in the

property dispute remembered Harris saying that he wished old man Bauguess

would pay him back, but that never happened.

Charles Harris died on July 5, 1849, of tuberculosis in Wilkesboro

where he had spent the past few days.

He was buried there at the Episcopal Church while it was still under

construction. Robert Bauguess is my distant uncle. References John Long and wife v Robert

Baugas, June 1842 (NC Supreme Court Cases) https://digital.ncdcr.gov/digital/collection/p16062coll14/id/39468 Robert Borgus v Owen Hall

and others, August 1857 (NC Supreme Court Papers) Martha/Patsy Martin Will,

proven August 1836, (Will Book 4, p206) https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:S7WF-336T-D9?i=310&cc=1867501&cat=293683 Iredell County Superior

Court, September 1841, (Minutes Vol 1, p551) https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4R-592T?i=310&cat=157095

Comments? jason@webjmd.com |