Blog

Article List Home My Research Services Contact Me

|

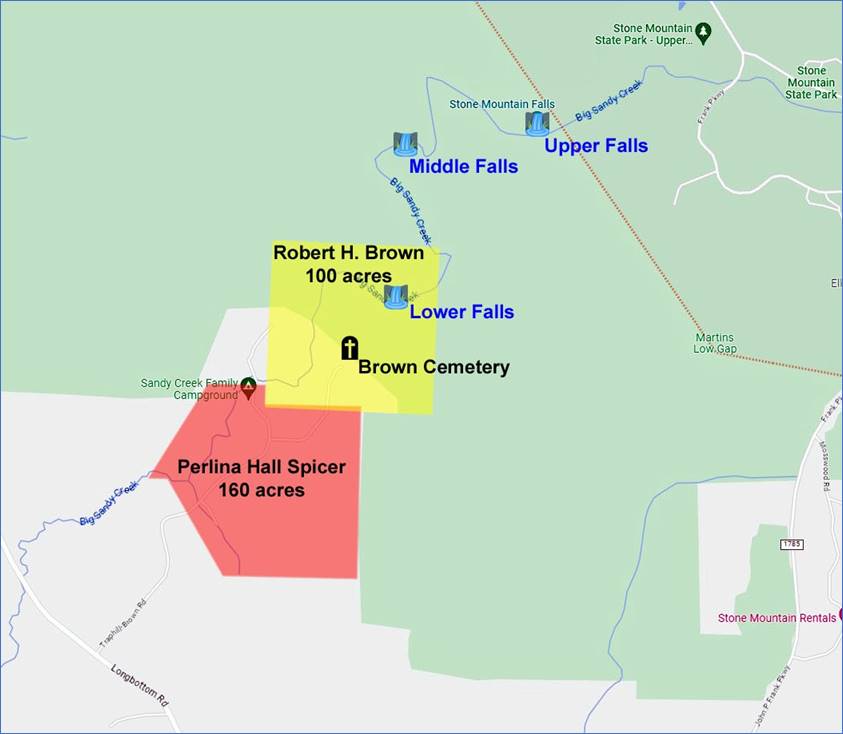

Wilkes June 8, 2023 The Dispute Below The Falls

– Brown vs Spicer On January 20, 1876, Richard Brown stood

out in the cold as he observed the county surveyor Larkin C. Brooks and

deputy surveyor Wesley Joines surveying his 100-acre tract of land at the Lower

Falls on the south side of Stone Mountain.

He had owned this land for twenty years, and he wanted confirmation

about where the four corners were located.

Everything started out fine while marking the north side of the

property, but when the surveyors moved south while marking the western

boundary, they were stopped by Zachariah Spicer who forbid them from crossing

his fence. The survey would not be

completed today.

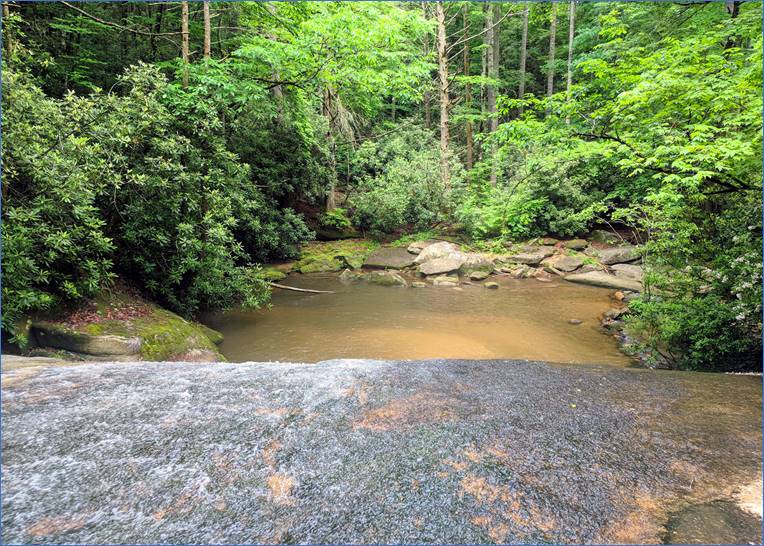

The

Lower Falls at Stone Mountain. As was the standard practice, when

surveyors were met with a disapproving land owner, they didn’t engage in the dispute. They packed up their equipment and reported

the incident to the court which would determine how to proceed with the

property boundary dispute.

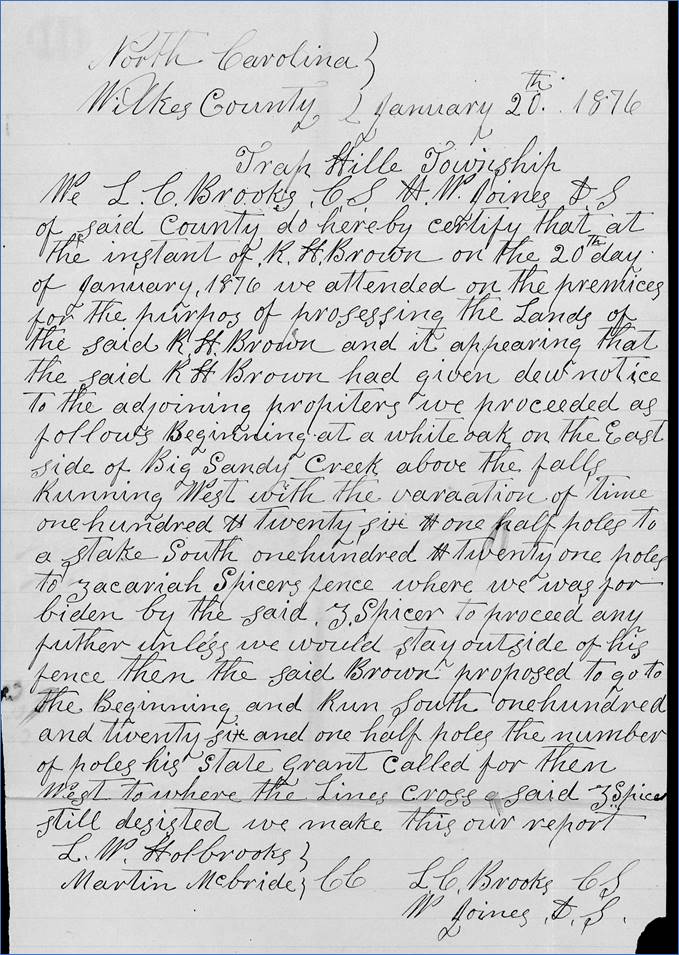

The

surveyor’s report from Brooks and Joines describes their surveying attempt in

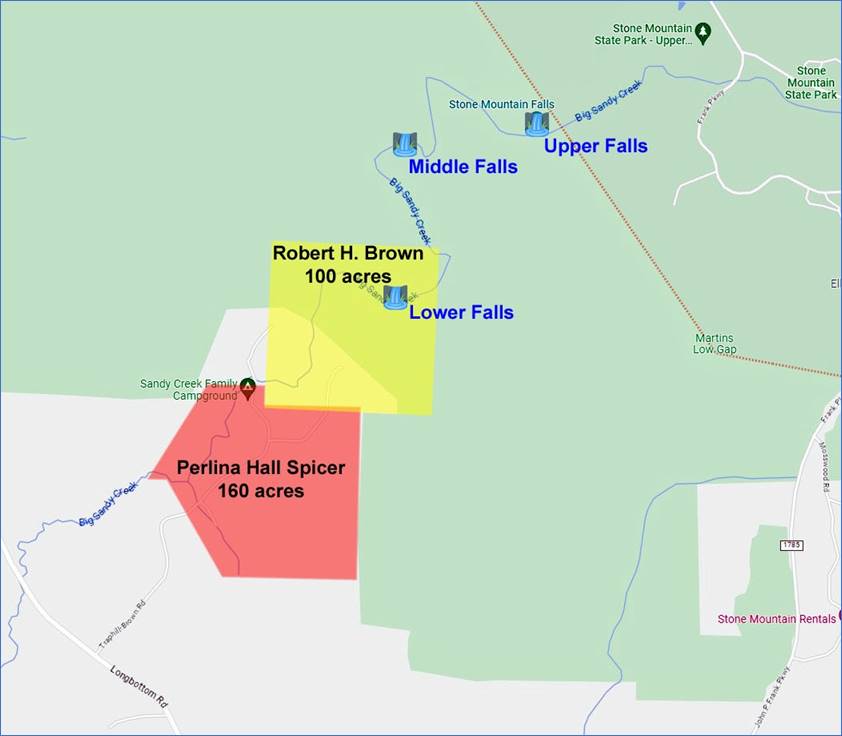

January 1876. Richard Brown’s Property Richard H. Brown owned over 500 acres

at Stone Mountain in the mid-1800s including most of the trail that leads

from the Hutchinson Homestead out to the Upper Falls. His property included the entirety of the trails

that lead to the Middle and Lower Falls, extending south to a point just

beyond the park’s boundary at the end of Traphill-Brown Rd. One particular tract of land that he

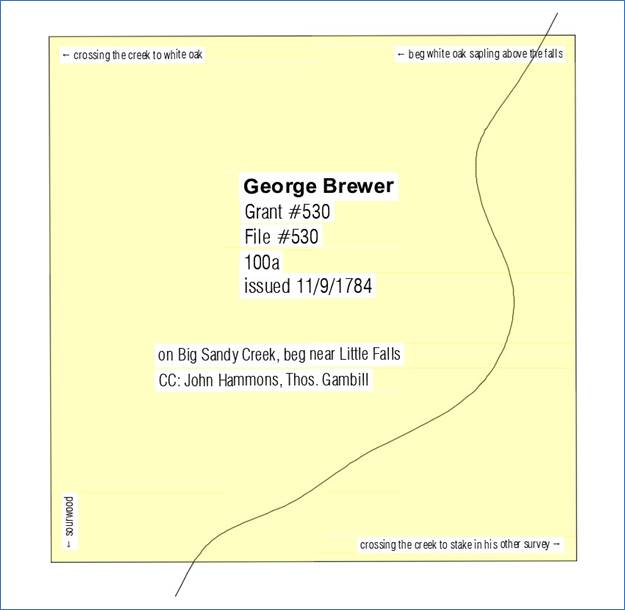

owned was for 100 acres which included the Lower Falls. It was originally granted to George Brewer

in 1784.

The

original 1784 land grant for the 100 acres describes it as being on Big Sandy

Creek near the “Little Falls”. George Brewer lost this land in 1796

when it was sold by the sheriff to Benjamin Adams. The deed (DB, p97) says that the court

ordered the sale of Brewer’s land to “cause to be made the sum of twelve

pounds, eighteen shillings, 11 pence which was recovered against him the said

George Brewer by Stephen Holiway”.

Apparently Brewer owed Holloway a sum of money, and Holloway took him

to court to get it. (As a side note, Stephen Holloway was Brewer’s

neighbor. Stephen Holloway – the progenitor

of all the Holloways of Wilkes County – was the first to live at the site of

the Hutchinson Homestead, even though he never officially purchased that

land. It was first bought from the

state in 1817 by John Brown who was the father of Richard H. Brown. Later, in 1858, John Hutchinson bought that

land where several generations of his family would live.) Returning to the 100-acre tract that is

in dispute, it was owned by William Williams until 1814 when he sold it to

William Edwards. William Edwards sold

it to Richard H. Brown in 1856. And in

1876, we’re standing out in the cold as the surveyors are packing up their

transits, compasses, and chains after being unable to complete the

survey. So why was Richard having his

property surveyed 20 years after he purchased it? Zachariah Spicer I checked the deed book indexes, but

there aren’t any deeds listed to or from Zachariah Spicer in this time

period. My first thought was that

these deeds must be missing. We know

Zachariah Spicer existed because he is listed in the censuses. He was born in 1852 and married Micah

Paulina Hall on August 26, 1875. Only

eleven months before their marriage, Paulina had inherited part of her father’s

estate which consisted of 160 acres on the southern border of Richard Brown’s

land. Therefore, Zachariah Spicer

never purchased the land. Instead, he

acquired it with his marriage to Paulina.

Four months after his marriage, 23-year-old

Zachariah Spicer was causing trouble for his neighbor. I imagine that Zachariah was clearing land

and installing a fence on what he felt like was the northern edge of his

land. Perhaps Richard Brown, a generation

older, explained to him that he had crossed the property line and that he

should construct his fence a short distance to the south. Zachariah refused, so Richard Brown called

the county surveyor.

Paulina

Hall inherited 160 acres (shown in red) from her father Owen Hall in

1874. She married Zachariah Spicer in

1875. The Second Survey Attempt A month after their first attempt, the

surveyors returned with a court order to complete their work. This time, a larger crowd was present. In addition to the two surveyors, the court

appointed a jury to oversee the process.

This included Joseph S. Holbrook, Lewis W. Holbrook, Henderson McGrady,

J. Alfred Johnson, and Samuel Caudill.

Additionally, Zachariah demanded that he bring witnesses A. Wiles, James

H. Foote, and L. Upchurch. With enough men to field a football

team, the surveying began once again.

Everyone agreed with the starting corner which was a white oak above

the falls of Big Sandy Creek. When they ran south along the west line, they

crossed Zachariah’s fence and ended at a sourwood stump in his field. Just as Richard Brown had said, Zachariah’s

fence was too far north.

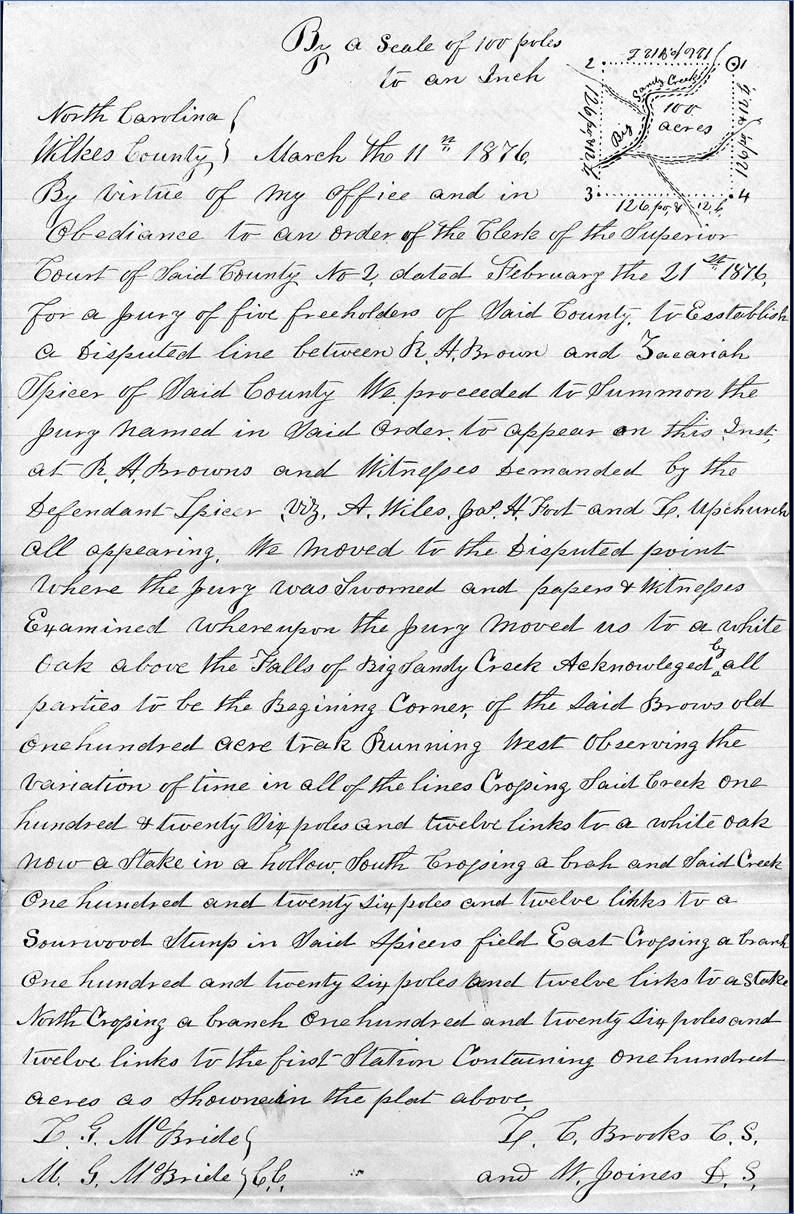

Surveyors’

report from their second attempt on February 21, 1876. Notice the small sketch in the upper

right corner of the report (and reproduced below). It shows the 100-acre tract with Big Sandy

Creek running through it. The northeast

corner is the beginning white oak. The

surveyors moved west to the the second corner, then south to the third corner

where they ran into Zachariah Spicer’s fence.

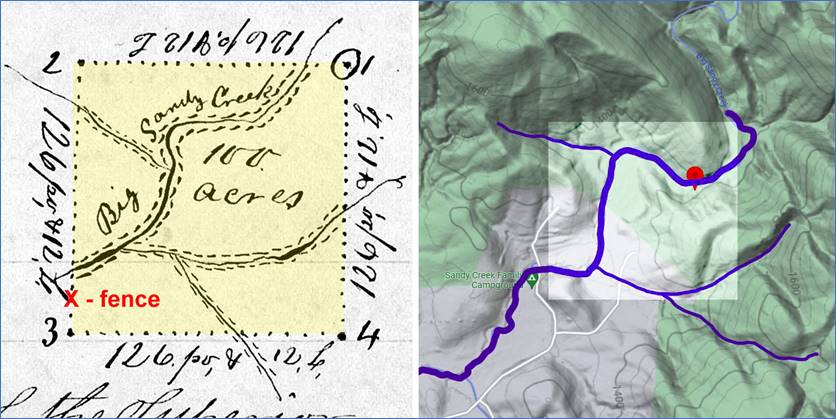

Comparison

of the survey sketch and the topo map. When comparing the survey sketch with a

topo map from today, the tributaries of Big Sandy Creek line up surprisingly

well! The third corner, which came to

a sourwood stump in Zachariah Spicer’s field, is still a field within Sandy

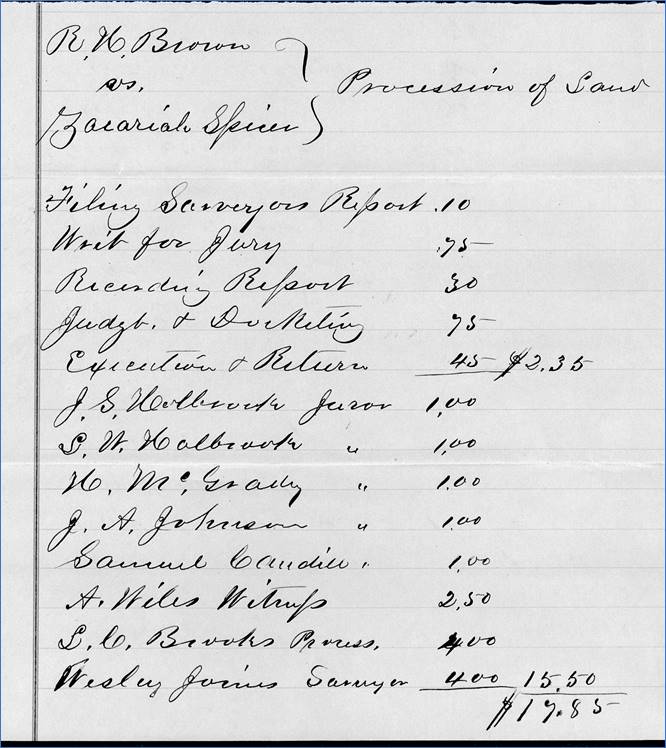

Creek Family Campground. The cost of the survey, with all of the

reports and witnesses, was $17.85.

While the court papers don’t state who paid these fees, it was likely

Zachariah Spicer since he was in the wrong.

The

cost of the survey was $17.85. Richard Brown’s Mill One other surprise that is revealed in

these records is the fact that Richard Brown owned a mill on this

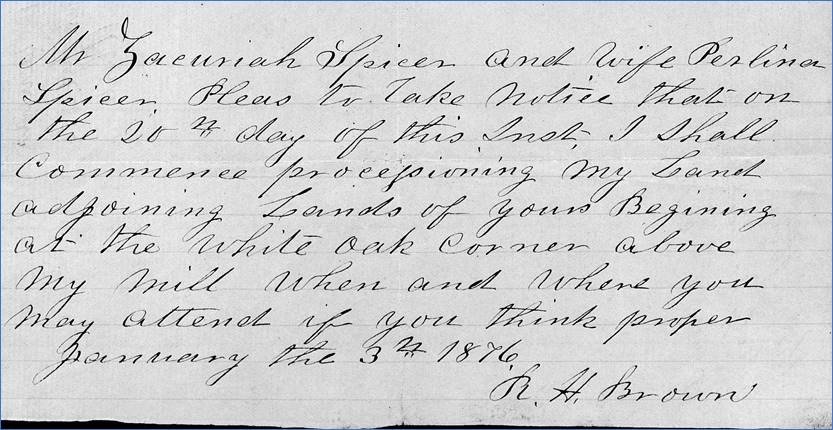

property. When Brown notified

Zachariah Spicer about the upcoming survey, he described the meeting point as

“the white oak corner above my mill”.

In the original 1784 grant, it was “the white oak above the little

falls”. So perhaps Richard’s mill was

located very close to the cascade that we know as the Lower Falls.

Zachariah

Spicer was notified of the upcoming survey in January 1876. One other landmark within this 100-acre

tract is the Brown Family Cemetery. It’s

at the south end of the state park, overlooking a field not far from his

disputed corner.

The

Brown Family Cemetery is located on Richard Brown’s 100-acre tract. Richard H. Brown (1830-1901) is buried

here with his wife Mary Joines Brown (1827-1914), along with several of their

children and grandchildren.

The

Brown Family Cemetery, looking south from the edge of the state park.

Headstones

for Richard Brown (1830-1901) and his wife Mary Joines Brown (1827-1914).

Comment below or send an

email - jason@webjmd.com |