Blog

Article List Home My Research Services Contact Me

|

Wilkes December 5, 2023 The Rebellious Riley Hall He peaked through the window of the

cabin, keeping his back pressed against the wall while looking over his right

shoulder through the glass. He held his

rifle upright with his left hand. No

signs of trouble. Riley Hall was

accustomed to being on high alert for a possible enemy attack, but these

days, it seemed like the enemy was everywhere, and everyone. Not only had he given his neighbors good

reasons to despise him, but within the past year he had fought against both

the Union Army AND the Confederate Army.

He was running out of safe places to hide. There was no sign of anyone

outside. No moving branches caused by

someone lurking at the edge of the woods.

The sun would be rising soon.

It was best that he go outside to check on things before

daylight. It would be harder to remain

hidden after the sun was up. He was

thankful that he wasn’t alone this morning.

He had someone else staying with him, maybe someone he had served

with, or maybe a relative. We don’t

know his name. There was safety in

numbers, right? He moved to the front

door and cautiously opened it.

Deciding that the coast was clear, he and his friend stepped out onto

the front porch.

Before The War Riley Hall was born about 1830, most

likely the son of Rachael Hall and Reuben Hayes. His parents weren’t married, but they lived

on adjoining farms in Mulberry on the south side of what is now Elledge Mill

Rd between Hwy 18 and Mulberry Creek.

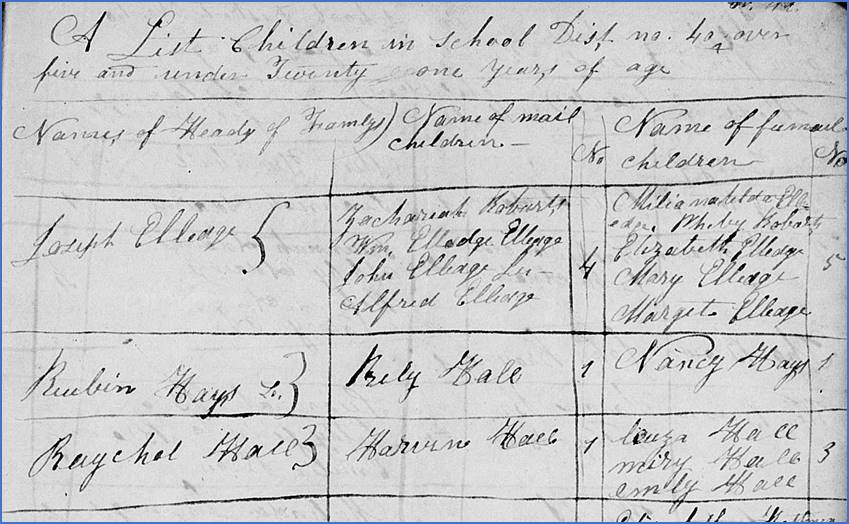

In the 1840 school census, Riley Hall was listed as a child between

the ages of 5 and 21, with Reuben Hayes as the head of household. On the very next line, Raychal Hall was the

head of household, listed with four school-age children.

Reuben

Hayes and Rachael Hall were both listed with school-age children in 1840. In the 1850 census, “Riley Hayes” was

still listed with the Reuben Hays Jr family, now as a 21 year old. This is the last time he used the surname

Hayes; going forward, he consistently used Hall, his mother’s maiden name. The next year, on Christmas Day 1851,

Reuben R. Hall signed a bond to marry Milly (Lunceford) Yates. While they were about the same age, this

was Milly’s second marriage. Her first

husband David Yates had died only a few weeks earlier in November. He had been nearly 40 years older than she

was, and their marriage only lasted seven months before his death. Yes, the year of 1851, had been crazy for

Milly! She had married, become a

widow, and remarried all within an eight-month period. Two years ago I wrote an article about Riley and

Milly and their connection to the Yates and Bauguess family. Back then, I didn’t know as much about

Riley’s adventures as I do now. Riley Hall Goes To Court Riley Hall must have had a hot temper

that was easily set off. While I

haven’t looked at court records in the first half of the 1850s, he was

certainly familiar to criminal court judges between 1856 and 1861. On August 7, 1858, Riley R. Hall was

summoned to appear at the next court session regarding a case where Henry

Brewer was fearful of his life because of threats from Willis Higgins. Riley wasn’t the accused party here, but

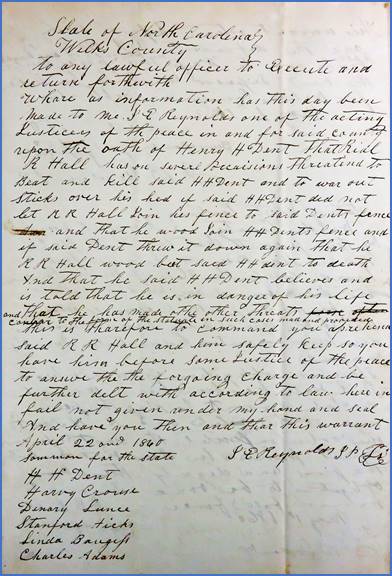

this is an early sign of the persistent drama that would surround his life. On April 22, 1860, Henry H. Dent

accused “Rial R. Hall” of threatening to kill him. He said Riley promised to beat him in the

head with sticks if Dent didn’t allow him to join their fences together. A week later, Riley paid bond with the help

of Reuben Hawkins so that he wouldn’t have to remain in jail until the next

quarterly session of court. In

September, the court found the indictment “not true”, leaving us to wonder

what actually occurred between the two men. A portion of this accusation by Henry

H. Dent reads: ...upon the oath of Henry

H. Dent, that Rial R. Hall has on several occasions threatened to beat and

kill said H. H. Dent and to war [wear] out sticks over his head if said H. H.

Dent did not let R. R. Hall join his fence to said Dent’s fence, and that he

would join H. H. Dent’s fence, and if said Dent threw it down again, that he,

R. R. Hall, would beat said H. H. Dent to death, and that said H. H. Dent

believes and is told that he is in danger of his life, and that he has made

other threats.

On

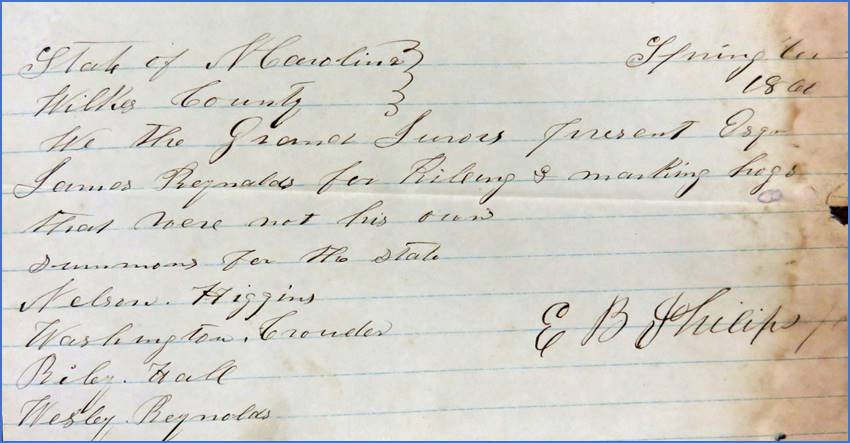

4/22/1860, Henry H. Dent accused Riley Hall of threatening him. At the Spring 1860 court session, Riley

Hall was again summoned as a witness for the State in the case of the State v

James Reynolds for killing and marking hogs.

Apparently these were Riley’s hogs because on September 1, 1860, a

different document accuses James Reynolds of the same thing against Riley.

In

the spring of 1860, James Reynolds was charged with killing and marking hogs. The 1860 census lists the household of

R. R. Hall. He is 29 years old with

wife Milly (age 30), and children Martha (6), Charles (3), and Jerusha

(1). Also in the household is Henry

(age 14, mulatto). Living next door to

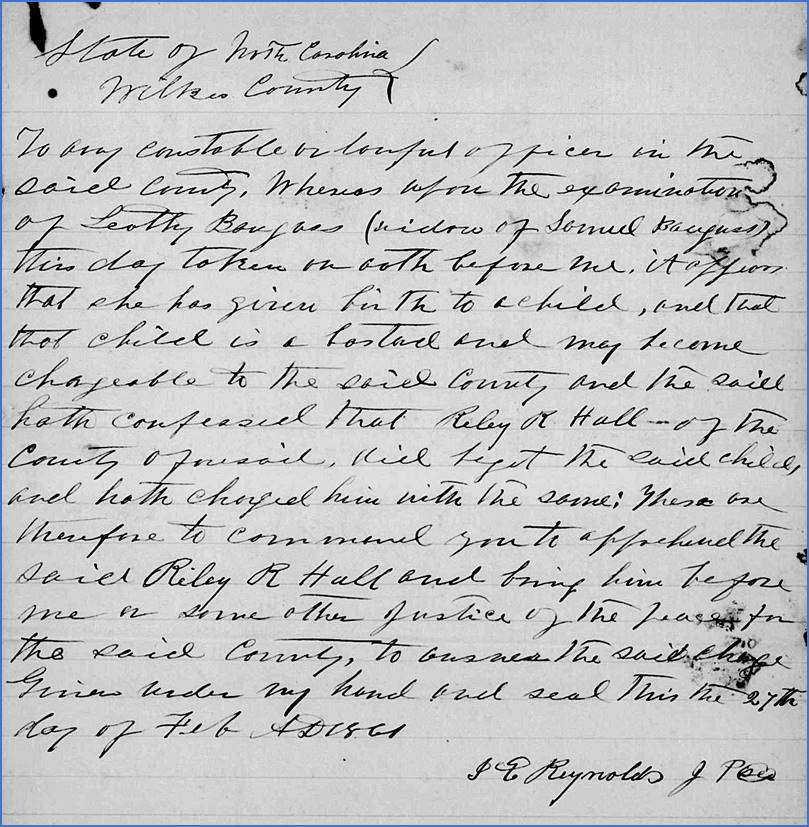

them is Riley’s mother Rachel Hall (age 47). Life Gets More Complicated On February 27, 1861, Riley R. Hall was

charged with having a child with Letha Bauguess, the widow of Samuel

Bauguess. Letha Yates Bauguess was ten

years older than Riley, and she was divorced from her husband Samuel when he

died the previous year. She had seven

children, and it’s unclear if Riley’s child was the seventh, or if his was

the eighth. Letha never remarried, and

she had very little means of supporting her children. Riley was charged with maintaining their

child, but it seems unlikely that he actually did so.

Riley

R. Hall was charged with having a child with Leatha Yates Bauguess in

February 1861. At the March 1861 term of court, R. R.

Hall, Reuben Bauguess, and Henry Bauguess were ordered to appear at the

September court as witnesses in the case of the State v Charles Adams and

Malinda Bauguess who were charged with adultery. During that same court session, R. R.

Hall was charged with assaulting Alexander Robison. If you’re keeping score at home, during

the span of one year, Riley had been charged with assault, threatening to

kill his neighbor, and bastardy. His

list of enemies was beginning to grow, and these weren’t just your average

enemies. Henry H. Dent was a Justice

of the Peace, as was James E. Reynolds whom Riley had accused of stealing his

hogs. Both men held a lot of power in

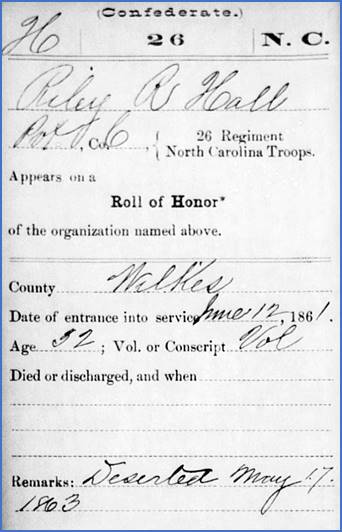

the county, and this would later come back to haunt Riley. Time To Leave Town On June 12, 1861, Riley R. Hall

enlisted at Wilkesboro as a Private in the 26th NC Reg, Co C. He did this voluntarily, and was among the

first to do so. It had only been three

weeks since North Carolina had joined the Confederate States. It’s possible that Riley was especially

passionate about the Confederate cause, or maybe Riley saw this as an

opportunity to make his problems go away.

By joining the Confederate Army, he could leave town with a paying

job, and when this skirmish was over, he would return home with everyone

having forgotten his sins. If that was his plan, he would be

greatly disappointed. But in the short term, his plan was

working perfectly! In the days before

he left with his regiment, he still had court battles to face. On June 24, 1861, Riley R. Hall was accused

by James E. Reynolds of threatening to kill him. Riley and Reuben Hayes (his father?) posted

the bond, and he avoided jail time. He

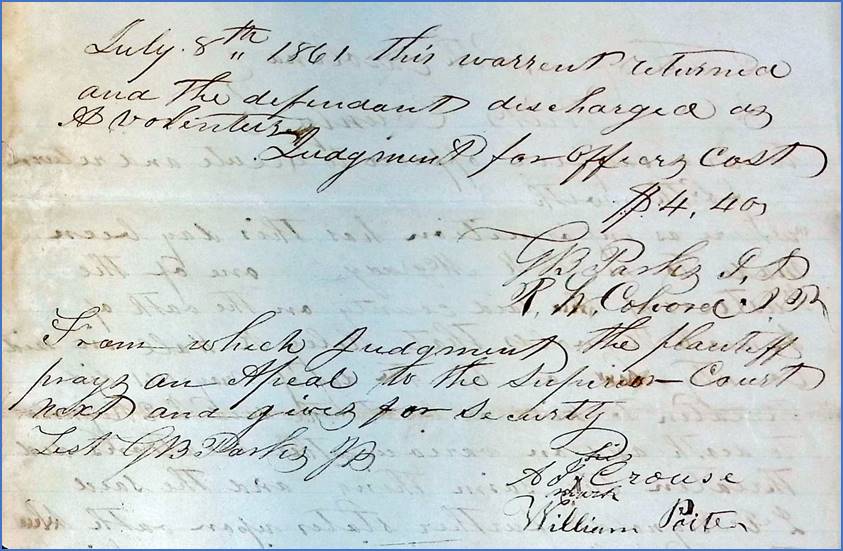

was due to appear in court on July 8, but a note on the back of the arrest

warrant says “this warrant returned and the defendant discharged as a

volunteer.” Reynolds clearly wasn’t

happy that the charges had been dropped simply because Riley joined the army. He asked that the judgment be appealed at

the next Superior Court.

On

July 8, 1861, charges against Riley R. Hall were dropped for threatening

James E. Reynolds. On September 1, 1861, the charges

against Riley Hall for assaulting Alexander Robison were dropped. Even though he had been indicted, it was

found to be “not a true bill”. Free from his court appearances, Riley

was listed as present in his regiment from September to December 1861. Likewise, he was present in March and April

1862. In September 1862, Riley Hall

and Reuben Bauguess were set to appear in Wilkes County Court, perhaps

regarding the previously mentioned adultery case which had been postponed. The sheriff reported that the two men were

not to be found in the county. That is

true. Both of them were still attached

to the 26th Regiment, and in late 1862, they were stationed in

eastern Virginia and northeastern North Carolina. They had endured some significant battles

during the past year, and there were likely times when Riley had second

thoughts about his eagerness to join.

Of course, if he hadn’t joined voluntarily, he would have been

conscripted eventually. From October 10 until November 23,

1862, R. R. Hall was listed with rheumatism in Episcopal Church Hospital in

Williamsburg, VA. After that, the next

mention of Riley on the muster rolls is on March 17, 1863, when he is listed

as a deserter.

Riley

R. Hall, age 32, was listed as having deserted on May 17, 1863. Riley deserted his regiment a month and

a half before the brutal battle of Gettysburg which occurred from July 1

through July 3, 1863. Exact numbers vary,

but they’re all extremely tragic for the 26th Regiment. Out of 800 men that entered the battle, 588

were killed, wounded, or missing after the first day of fighting. The second day was mostly a day of rest and

regrouping. On the third day, the 26th

lost another 100 men. More than 80% of

the soldiers in the regiment were killed or disabled at Gettysburg. A New Beginning It’s a year later when Riley makes his

next appearance in the records. On

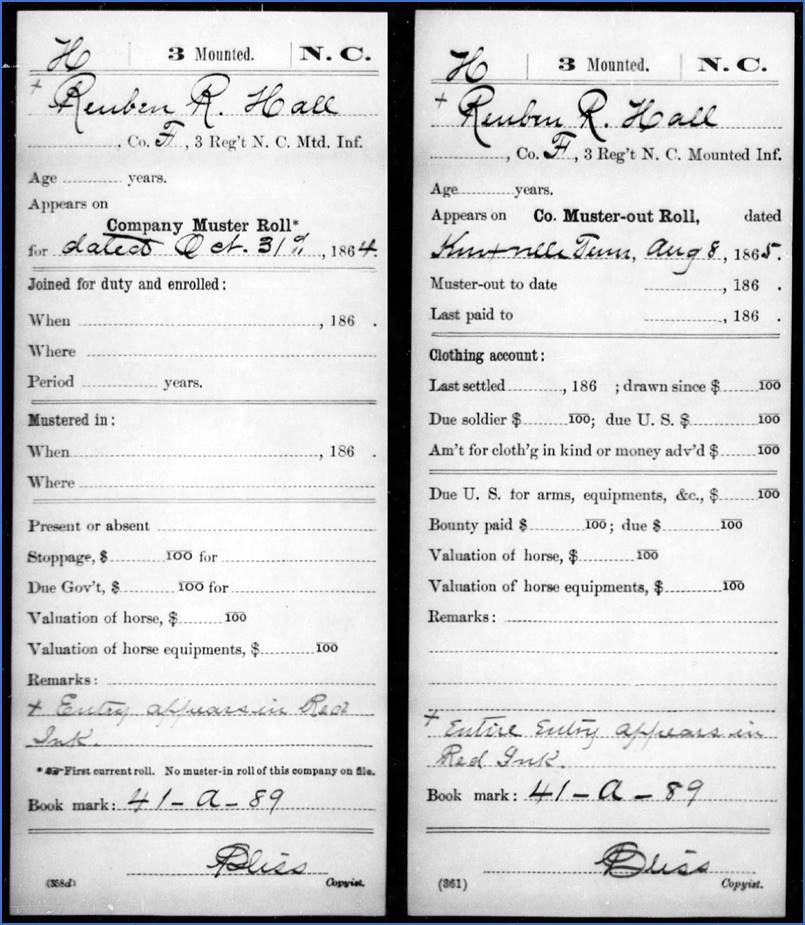

October 31, 1864, Reuben R. Hall is listed on the muster roll of the 3rd

Reg NC Mounted Infantry, Co F. The

document doesn’t state when he enlisted.

A separate document lists him on the “Muster-out Roll” dated August 8,

1865, at Knoxville, TN.

Left: R. R. Hall was present for muster on

October 31, 1864. Right: R. R. Hall was mustered out on August 8,

1865 when the regiment disbanded. Sometime between his desertion in May

1863 and October 1864, Riley Hall had made his way into northeastern

Tennessee to enlist with the Union Army.

This infantry was formed in February 1864 entirely of volunteers who were

Union loyalists from North Carolina and parts of Tennessee and Virginia. Their mission was to use guerilla tactics

to destroy as much of the Confederate transportation routes as possible. They were known as Kirk’s Raiders under the

command of George Washington Kirk. They

caused destruction in eastern Tennessee, Morganton, NC, and as far east as Salisbury,

NC. One of their missions was to

protect Deep Gap and Watauga Gap near Boone to make way for Stoneman’s troops

in March 1865. The document above makes it appear that

Riley stayed with his regiment until the end of the war when Union troops

were released on August 8, 1865.

However, the next part of the story makes it sound like he might not

have made it that long. Back At Home Now we’ll return to the point where we

began this story – at Riley Hall’s home in Mulberry, just before

sunrise. After checking the windows

and cautiously opening the door, he and his unnamed friend stepped out onto

the porch with their rifles in hand. Unbeknownst to them, a search party had

formed the previous night in search of Riley Hall who was wanted by his

neighbors for having deserted the Confederate Army. Perhaps it’s best if we let this part of

the story be told by John A. Ward who was part of that search party. These undated papers were found among

Wilkes County court records, and they describe a tense situation in pursuit

of Riley Hall. I (John A. Ward) being at

Wilkesboro was summoned by Lt. Boushell to report at Mr. Hunt’s below

Wilkesboro that evening for the purpose of taking up deserters and was led by

Boushell to William Emerson’s ___ __ and by the way of Jas. E. Reynolds’ for

the purpose of getting them in the squad and they refused to go thus by way

of Wesley Felts. And then got Wm.

Johnson and then all went to Mr. Dent’s and there Lt. Boushell summoned Mr.

Dent to go with him that night to which Mr. Dent replied we had better wait

until morning, then I will go with you.

Then we got up in the

morning something like an hour and a half before day at which time Lt.

Boushell asked how far it was to R. R. Hall’s. He also was asked if there was any private

way they could go without being seen.

Mr. Dent answered there was, then Mr. Dent was ordered to lead them

that way by Lt. Boushell, and we arrived at the place between day light and

sun up. Then Lt. Boushell asked if

there was any way of getting out from the house on either side, and Mr. Dent

answered there was. Then Boushell

taken three and went over on the left and ordered the other four to guard the

path on the right which order we obliged, and was ordered to take any

deserter that might pass that way, dead or alive. We seen two men start out

from the house toward where we was stationed, one with a gun who was supposed

to be Hall. They both came up within

some five or ten paces from where we was in readiness with our guns cocked. We halted them at the word halt. Hall faced toward us and was in the act of

presenting his gun cocked at which time two guns were fired. Hall then dropped his gun

and run about twenty or thirty yards at which time Dent busted a cap. That James Hunt and Felix Petty said they

shot, they belong to our squad. Hall

ran about two hundred yards and fell wounded.

Said Ward was asked on

examination if Dent shot Hall, and answered he did not. Mr. Ward states that he proposed that if

they were compelled to shoot, that they should shoot so as not to kill, to

the squad agreed. That’s quite a story! You can view all three images of the original

document here: Image 1, Image 2, and Image 3. The men mentioned in the deposition

were likely part of the local Home Guard which was made up of men who were somehow

exempt from joining the Confederate Army.

They might have had a medical condition that prevented them from

serving, they might have been too old to be required to serve, or they might

have been deemed essential to the local community. In any case, the Home Guard often acted

with violence and behaved as as if they were above the law. John A. Ward provided the story, and I

don’t know who he was. There was a man

by that name from Watauga County who was born in 1829. He is said to have died in 1865 during the war. His deposition begins, “I, being at

Wilkesboro, was summoned...”. That

makes is sound as if he was from out of town.

Maybe he had come down the mountain in search of Confederate deserters

who had joined the Union Army in nearby Tennessee. Two men mentioned in the account were

Henry Dent and James E. Reynolds. We

recognize both of them as being a Justice of the Peace who each had legal

disputes with Riley Hall before he joined the army. I imagine they were more than happy to assist

in apprehending him, although it’s not clear if Reynolds accompanied them on

the man hunt. James Hunt and Felix Petty may have

both shot at Riley based on Ward’s account.

Depending on the year that this occurred, they both would have been

around 18 or 20 years old and part of very wealthy families. Perhaps they weren’t actively serving in

the Confederate Army because they paid substitutes to join in their places. More Questions The deposition of John A. Ward doesn’t

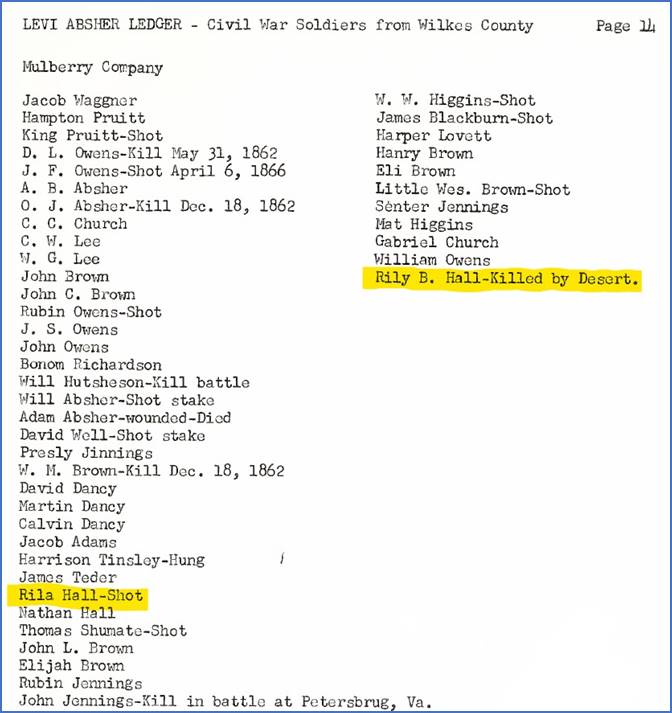

explicitly say that Riley Hall was shot and killed on this day. But I tend to think that he was. There is a diary known as the “Levi Absher

Ledger” that was maintained by Mr. Absher to record notable events in his

neighborhood during the Civil War.

While the original was handwritten, a typed copy is available for research. On the last line of the last page, an entry

says “Rily B. Hall-Killed by Desert.” Another

entry on the same page says “Rila Hall-Shot”.

The

Levi Absher Ledger has two entries for Riley Hall. The ledger has at least a few typewriter

errors among its 14 pages. Also, the

original handwriting was probably hard to read. I imagine that the middle initial in the “Rily

B. Hall” entry was actually an “R”.

Unfortuntately, Mr. Absher didn’t record the date of Riley’s demise. (I’d love to see the original ledger to see

if it reveals any other clues about these entries, but I’m not sure where it’s

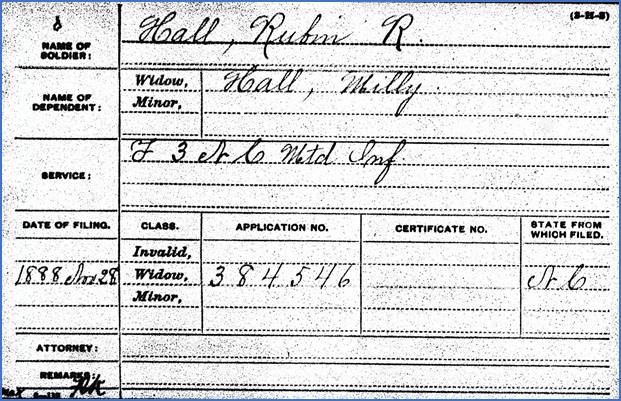

located or if it even exists.) We also have the widow’s pension

request filed by Milly Hall on November 28, 1888. It lists her husband as Rubin R. Hall who

served in the 3rd NC Mtd Inf.

1888

pension request filed by Riley’s widow, Milly Hall. I believe the stakeout at Riley Hall’s

cabin occurred sometime before April 1865 when the war ended. That means his muster out document (from

August 1865) was just a formality, and he wasn’t actually present when it was

filled out. There’s no reason to question his

October 31, 1864, muster, and I believe he was part of the Union Army on that

date. This means that Riley was shot between

November 1864 and April 1865. There are more court records for me to

go through, and I’m hopeful that I’ll find another paper that says when this

event happened. I’ll share it if I

discover anything new. If anyone else

has information to add to the story, take a minute to send me an email or

leave a note in the comments. *Note:

All of the Bauguess’s mentioned are my distant cousins. They are either grandchildren or great

grandchildren of my ancestor Richard Bauguess who settled in Wilkes County in

1789.

Comment below or send an

email - jason@webjmd.com |