Blog

Article List Home My Research Services Contact Me

|

Wilkes October 2, 2024 The Homes of Robert and

Benjamin Cleveland Robert and Benjamin Cleveland were two

of the nine children of John Cleveland and Elizabeth Coffey. In the 1760s, they left Virginia and came

with at least three of their siblings to the area that would soon become Wilkes

County. When they arrived, they selected

suitable locations to settle, built a cabin there, and started a farm. But one thing that they did not do

immediately was purchase land. The

British land office that was operated by Lord Granville closed about 1763

soon after his death. The North

Carolina state land office opened in 1778 during the Revolutionary War, and

many early settlers were quick to begin the process of purchasing land that

they had been living on for years. If

they didn’t buy it, someone else might beat them to it, forcing them off the

land that they called home. There were

often disputes amid the confusion over who the rightful landowners should

be. Meanwhile, with everyone

preoccupied with the ongoing war for independence, it must have been an

extremely stressful and chaotic time for the entire family. The 1798 Direct Tax List After the war ended, the new United

States established taxes to pay for the operation of a government, to fund

the creation of public buildings, and to repay both foreign and domestic

debts. In July 1798, the U.S. Congress

passed a bill to collect $2 million through a direct tax from the 16 states

to fund a military expansion. North

Carolina’s portion was determined to be $193,697.96. Landowners were taxed based on the total

value of land, dwelling houses, cabins, barns, mills, and other buildings on

the property. Slaves were taxed as

well. Each county was responsible for

collecting the tax and sending it to the state. According to the National Archives,

most of these tax lists have been lost and no longer exist. For North Carolina, only Iredell County is

listed as having an existing 1798 tax list, and these pages are scanned and

online as part of the UNC Wilson Special Collections Library, collection

number 03919-z. As of 2024, these Iredell County records can

be viewed online. While browsing through records among

the Lenoir Family Papers recently, I found county documents that included the

Wilkes County Direct Tax List from 1798.

Within the collection, these papers are in subseries 6.1.2, folders

672 through 674, and the originals are held in the Wilson Library at the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

This was an exciting discovery! The Wilkes County tax list was recorded

by William Lenoir beginning in 1798, and it certainly continued into

1799. The list of landowners was made

before Ashe County was created in the November 1799 session of the North

Carolina General Assembly. Any

soon-to-be citizens of Ashe County are included in this Wilkes County list. This tax list is an extremely valuable

resource for anyone interested in the history of northwest North Carolina

soon after the Revolutionary War. When

combined with the 1800 census, it becomes possible to reconstruct what this

part of the state looked like and how the population was dispersed among the

various watersheds. This will help

genealogists determine where their ancestors lived and what their homesites

were like. Archaeologists and

historians can use this information to determine how buildings were

constructed and how they varied in size among different communities. Mapmakers will find information that

identifies the names of creeks and branches on larger waterways. This is a treasure trove of information

that is rare for this time period. I transcribed the entire 1798 Wilkes

Tax List and compiled it into a book that is available for purchase at the

Wilkes Heritage Museum gift shop and online from Lulu.com. A

link to purchasing the book online is on my website. Robert Cleveland’s Log Home Capt. Robert Cleveland settled on the

North Fork of Lewis Fork, and his home is said to be the oldest home in

Wilkes County, having been built in 1779.

In the late 1980s, the house was disassembled and moved from its

original location and rebuilt in downtown Wilkesboro. Today, museum visitors can tour the home as

part of the Wilkes Heritage Museum property.

And now, the 1798 Tax List provides more details about what this home

was like when the family lived there. Robert Cleveland has four taxable

properties in this 1798 tax list, with a total of 441 acres of land. His homesite included a dwelling house, a

kitchen, and two slave cabins. He

owned 13 slaves, but only four of them were taxable. That is, four of his slaves were between

the ages of 12 and 50. The majority of

his other nine slaves were likely young children.

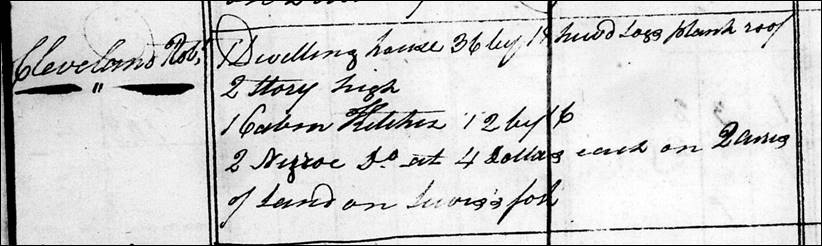

1798 tax entry for

structures on land owned by Robert Cleveland. Cleveland’s dwelling house is described

as being 36 feet by 18 feet, two-stories, made with hewed logs, and a plank

roof. Today, the cabin measures 35 ft

by 18 ft, and the two chimneys add a few more feet to the length. The hewed logs allowed them to fit together

more closely to create a more insulated wall.

The plank roof is an interesting detail because most homes at the time

had a shake roof. In fact, when the

home was reconstructed at the museum location, it was built with shakes. Before the house was moved, it had a tin

roof. I imagine that the plank roof

consisted of boards laid horizontally across the rafters, with each one

overlapping the one below.

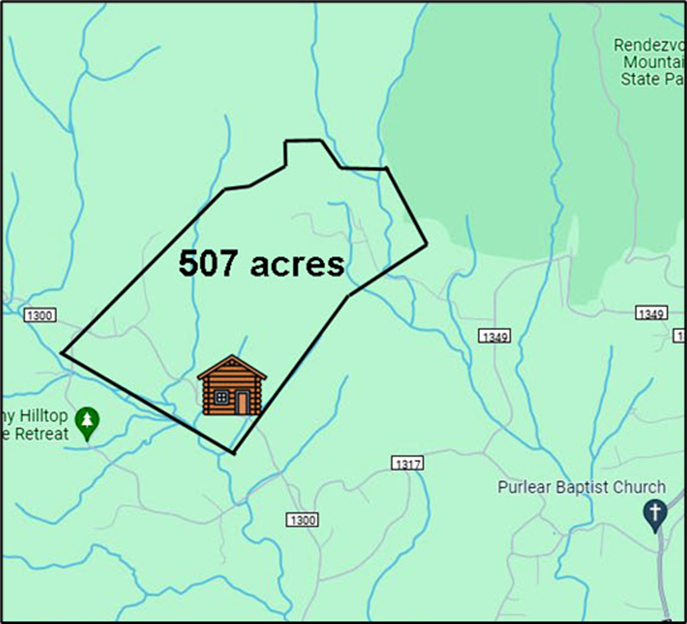

Robert Cleveland owned 507

acres. His home was 1.5 miles up

Parsonville Rd on Lewis Fork. This was an especially large house in

1798. It was one of only eleven houses

in the county that were two stories high.

By square footage, it was the fifth largest house in the county. Wilkes County was much larger then,

extending north to Virginia and west to the Tennessee border so that it was

two and a half times the size it is today.

This home would have seemed huge to most others who lived in the

county. The Cleveland family needed a large

house! In 1798, Robert and his wife

Sarah had ten children still living at home assuming that the fifth child

Presley (age 19) hadn’t moved out yet.

The youngest child Fanny was one year old.

Robert Cleveland home on

Lewis Fork, 1980s, courtesy of the Wilkes Heritage Museum. Benjamin Cleveland’s Roundabout Home Benjamin Cleveland famously lived at

the roundabout of the Yadkin River where the town of Ronda is today. He had “the Great Roundabout” tract

surveyed in 1778, and he was issued a grant for this land in March 1779. Between 1778 and 1785, he purchased 3,520

acres in land grants from the state of North Carolina. During that time, he was constantly buying

and selling tracts of land on both the Yadkin River and New River. Cleveland left Wilkes County and moved

to South Carolina about 1785. He had

been in the midst of a court battle over his Roundabout tract for several

years, dating back to before he was even issued the the land grant. In September 1778, William Terril Lewis

brought a case before the Wilkes Superior Court claiming that he was the

rightful owner of this valuable land.

Things were said and accusations were made, but Lewis won the

case. Cleveland experienced a rare

loss, and he was forced to give up Roundabout in 1786. I like to think that Cleveland was so

angry at losing this picturesque property that he stormed out of the county,

never to return. But that’s probably

not what happened. Benjamin Cleveland

owned a few thousand acres in what is now Wilkes and Ashe Counties, and he

certainly wasn’t homeless or destitute after losing Roundabout. The more likely story is that during the

war he was really impressed with land in the Tugaloo Valley in present day

Oconee County, SC, and he decided to make this his new home. He seems to have moved there a year or so

before the conclusion of his Roundabout case.

By the summer of 1785, he already owned more than 2,000 acres near the

Tugaloo River. Benjamin Cleveland fought for his

Roundabout plantation for eight years, and I’ve often wondered what his home

looked like. I imagine it was much

more substantial than most of the homes in the area, and even after he left

the state, such a prominent home would still be used by the later occupants. By the time of this 1798 tax list,

Cleveland had been gone from the state for 13 years. For most of that time, the Roundabout farm

had belonged to William Terril Lewis.

On November 9, 1797, James M. Lewis and William Terril Lewis Sr, both

of Tennessee, sold 560 acres “on the North side of the Yadkin River called

the Round About” to James Shepherd (Wilkes DB D, p318). James Shepherd was the owner when the tax

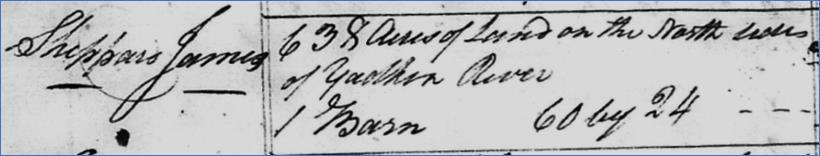

list was made in 1798. James Shepherd – written as James

Sheppard – has two entries in the tax list.

One entry is for the land, and the other is for the structures on the

land. Shepherd owned 638 acres on the

north side of the Yadkin River, and an extremely large barn was on that

land. In fact, it was the second

largest barn in the county, measuring 60 feet by 24 feet. Maybe this had been Benjamin Cleveland’s

barn!

In 1798, the first entry

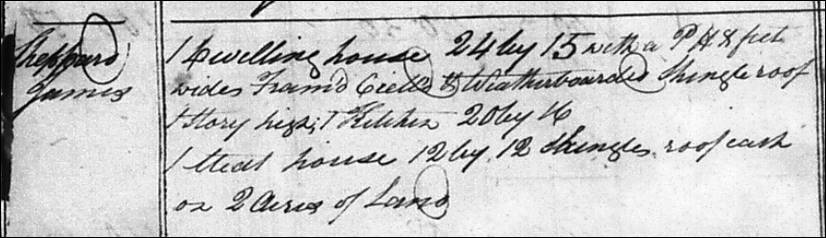

for James Shepherd shows his 638 acres of land and his 60’ x 24’ barn. The other entry for James Shepherd shows

that his homesite consisted of three buildings spread across two acres of

land. In addition to a modest kitchen

and a small meat house, he owned a dwelling house that measured 24 feet by 15

feet. It was a one-story structure,

sealed and weatherboarded, with a shingle roof. Very few houses were described as being

“sealed and weatherboarded, so this was a nice house even though it wasn’t

especially large. It also had a “PH”

that was 8 feet wide along the length of the house. I can only guess that this was some type of

porch. Only two other houses in the

tax list were described as having a “PH”.

1798 tax entry for

structures on land owned by James Shepherd at Roundabout. Could this have been Benjamin

Cleveland’s house? I’m undecided, but

I’m tempted to think that it was. With

Cleveland’s large, powerful, and commanding personality, I want to give his

home the same characteristics. Surely,

he must have lived in one of the nicest and most expensive homes, ready to

entertain influential guests with the latest amenities whenever the need

arose! But we don’t have enough information to

make a fair comparison between Ben’s house and others in the area. The best we can do is to compare Benjamin

Cleveland’s (possible) 1785 home to all of the homes in the county in

1798. Over those 13 years, a lot had

changed in this part of the state.

People had begun to set up stable homesteads after the end of the war. They were transitioning from frontier

settlers to growing families with towns and a stable government. The average home in 1798 was almost certainly

larger and nicer than the average home in 1785. Likewise, the grandest home in 1798 would

have been much more substantial than the grandest home in 1785. Going one step further, Cleveland’s home

was likely built long before 1785, perhaps in the 1770s or even in the late

1760s soon after his arrival. With

that in mind, Cleveland’s first house – and perhaps his only house – along

the Yadkin River would have appeared much less impressive when compared to

all of the other homes in 1798. Simply

put, it was becoming outdated. It was during and soon after the war

that Cleveland gained increased distinction and glory. That is when we would expect him to build a

new, larger home that would make a powerful statement among his neighbors and

celebrate his success. As an example,

William Lenoir was a captain who served under Col. Benjamin Cleveland at the

Battle of Kings Mountain. They lived

only a few miles from each other during the war. Afterwards, Lenoir moved westward up the

Yadkin River and began building his impressive Fort Defiance home in

1788. But since Cleveland moved away,

he wasn’t here to renovate and improve his plantation like his neighbors

were. Perhaps this 1798 home WAS

Cleveland’s old home, and in the years since he left, it was no longer

remarkable. His old home was merely

average when compared to others built over the next 13 years. Finally, I can’t imagine the next

landowner tearing down Cleveland’s comfortable house and building this 24’ x 15’

house in its place. That seems

wasteful and not really much of an improvement to justify the cost. Of course, there’s always the possibility

that a fire destroyed Cleveland’s Roundabout house sometime after he

left. In that case, the house listed

in 1798 would have been a replacement for the one that Cleveland had lived

in. Whether this was Cleveland’s home or

not, I’m confident that he lived in a very comfortable house for the time

period. It would have been warm,

weatherproof, and well-built. After

all, he was the colonel of the county militia, and he held several high-level

government positions that paid very well.

Until more documents are found, this might be the closest we get to

learning about Cleveland’s home at Roundabout.

Comment below or send an

email - jason@webjmd.com |