Blog

Article List Home My Research Services Contact Me

|

Surry February 25, 2022 Elkin History – Part 2 Part 1 ended with theories on the

origin of the name “Elkin”. This next part

is about an early settler who made a lasting impact in the community. I’m thinking this will be a four-part

series, but who knows? It might be

longer. All of these articles are

listed on my Elkin History page

and also here: Part 1 –

Theories on the Origin of the name “Elkin” (1760s – 1790s) Part 2 – [this article] Part 3 – Mills and

Factories at the old iron works site on the Big Elkin (1840s – 1950s) Part 4 – Bridges on the Yadkin River

and Big Elkin Creek in Photos (1860s – 1930s) [coming soon] Looking back at Elkin's history, it's

almost as if there was an early settlement that existed before the one most

of us are familiar with. Many of the

first settlers in Elkin – and I'm using the name Elkin loosely since the town

itself wasn't incorporated until 1889 – only stayed a few years before moving

farther west as the new country began to grow. Silveness Pipes, Joel Lewis, Ichabod

Blackledge, William Carrell, and Michael Vanwinkle each owned over 100 acres

in Elkin in the 1780s, but their names aren’t found in the records after the

early 1800s. Another name to include in that list of

early settlers who moved away is David Allen.

He was certainly one of the very first settlers in Elkin, and he made

quite an impact on the area. It was on

land originally owned by David Allen that Richard Gwyn set up his first grist

mill on the Big Elkin Creek. The

mill’s success led to textile factories that eventually culminated in Chatham

Manufacturing. It led to the railroad,

the old shoe factory, a downtown, and many other businesses that grew into

the town we know today.

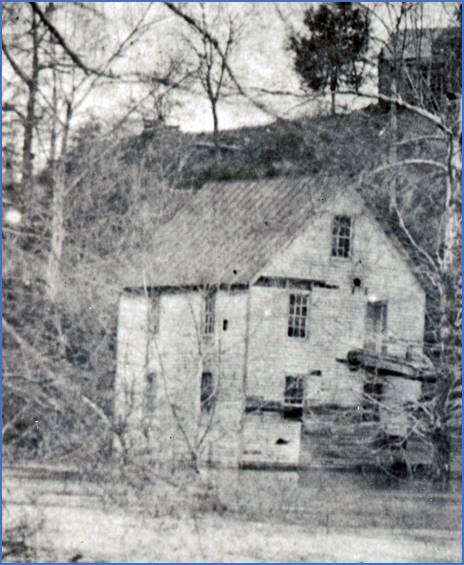

The 1840 grist mill was located on the

east bank of the Big Elkin Creek at the end of where the concrete dam is today. The hill behind it is where the elementary

school is now. This photo was taken

about 1898. A lot has been documented regarding

Elkin’s history since 1840, and there's a clear link between Elkin today and

the the Gwyn grist mill that started it all.

But the connection back to the history that occurred even earlier at

the very same location is not as well known.

While it’s been largely forgotten, these earlier events laid the

groundwork and provided infrastructure that was essential to the success of

these later endeavors. We’re fortunate

that there’s still plenty of evidence of this early history and its impact on

the community. David Allen Arrives About 75 years before Richard Gwyn

built his grist mill, David Allen arrived on the Big Elkin Creek in the early

1760s. He was about 50 years old, and

he had traveled from the colony of New Jersey with his family. This was at a time when the word “Elkin”

was first being used, and it’s possible that the creek he settled on didn’t even

have its name yet! He had only a few neighbors

within several miles, and he was situated on the western edge of the

frontier. Even though he was quite isolated,

he wasted no time setting up a business.

David Allen is first found in the

records kept by the Moravians. In

March 1768, two Moravian brethren traveled from Bethania to Isaac Free’s

ferry landing on the Yadkin River to pick up pine boards that would be used

to construct a house in the new town of Salem. The boards had been brought by David

Allen. The following month, they again

picked up boards that had been cut at Mr. Allen’s saw mill and floated down to

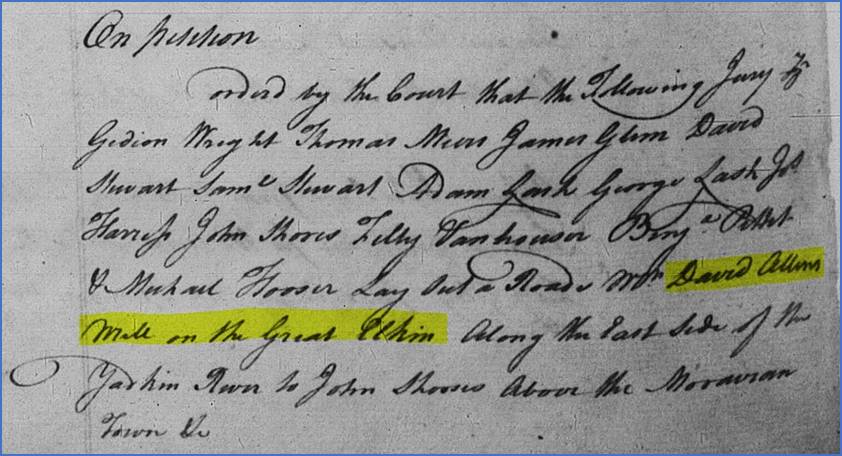

the ferry landing. The Rowan County road order below, dated

2/16/1769, refers to David Allen’s mill on the Great Elkin. Along with the 1768 Moravian records, this

is the earliest reference to a manufacturing operation at the place that

would become the town of Elkin. David

Allen was operating a saw mill, and if he was the most convenient source for the

Moravians who lived thirty miles away, there must not have been many options in

the area yet.

With it being the only large-scale business

for miles around, David Allen’s settlement became the center of attention for

those living along the Yadkin River west of the Moravians. In the 1760s and 1770s, Rev. George Soelle

traveled through the Yadkin River valley to preach to those in need. He kept a diary, and in September 1772, he

wrote about passing the Fox Nobbs (near Jonesville) and continuing on to

Pipe’s house in Allen’s Settlement.

John Pipes lived on the south side of the Yadkin River on Pipes Creek

(now Lineberry Creek) east of Jonesville.

The fact that Soelle called the area “Allen’s Settlement” is an

indication that David Allen’s operation was the centerpiece of this growing

community and that the settlement extended for several miles along both sides

of the Yadkin River. The Iron Works David Allen expanded his operation from

a saw mill to an iron works in the early 1770s. His knowledge of the lumber business and

his access to sawing equipment served him well when it came to cutting trees

for the massive amounts of fuel he would need for producing iron. The iron works business allowed him to sell

a valuable resource to a growing customer base as more settlers arrived in

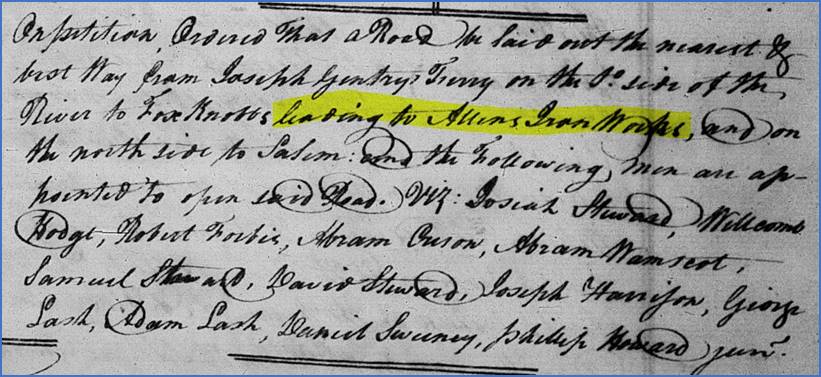

the surrounding area. A Rowan County

road order dated 2/4/1773 is the earliest mention of the iron works on the

Big Elkin.

The road order (Rowan Co P&Q Vol 4,

p8) is for a road to be laid out on the south side of the Yadkin River then

leading to Allen’s iron works and along the north side of the Yadkin to

Salem. David Allen was producing iron even

though it was prohibited by British law to do so in the American

colonies. The 1750 Iron Act, much like

the subsequent Stamp Act and Tea Act, restricted the independence of the

colonies. Its purpose was to keep

profits at home in England by suppressing the colonial manufacturing of

finished iron goods. These unfair acts

were not appreciated by the colonists, and they eventually led to the

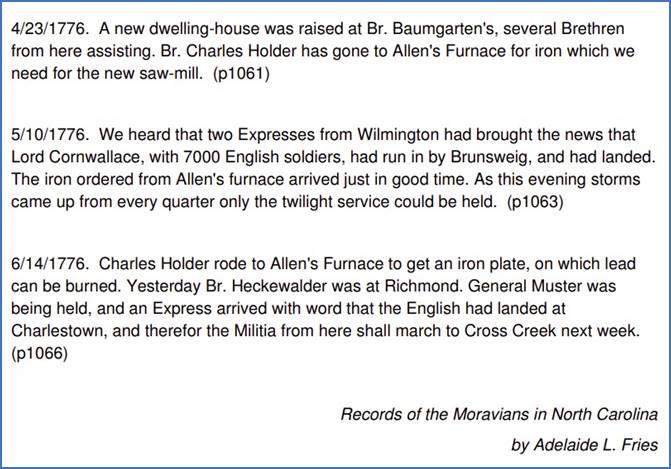

Revolutionary War. In 1776, David Allen is again mentioned

in the Moravian records, but this time as a supplier of iron. In three entries in April, May, and June of

1776, the Moravians recorded that they received iron from “Allen’s Furnace”.

In 1778, after the creation of a state

government to replace British rule, North Carolina began to sell land to

citizens. While some wealthier

settlers had purchased land from Lord Granville under the British system,

that process had been abandoned since the early 1760s. As families started settling in the state,

they had no choice but to make their homes on vacant land without filing any

paperwork or paying for the land.

There was no government office to handle the purchase. This was likely the case for David

Allen. He had been living on the Big

Elkin for more than a decade on land that he didn’t officially own when the

North Carolina Land Office began selling land in parcels of up to 640

acres. Since he was operating a

thriving business at this carefully chosen location, he certainly didn’t want

to lose what he had created. By 1781,

David Allen had purchased four large adjoining tracts of land in both Wilkes

and Surry Counties for a total of 2,482 acres. This was land that he had been using for

timber and mining since his arrival.

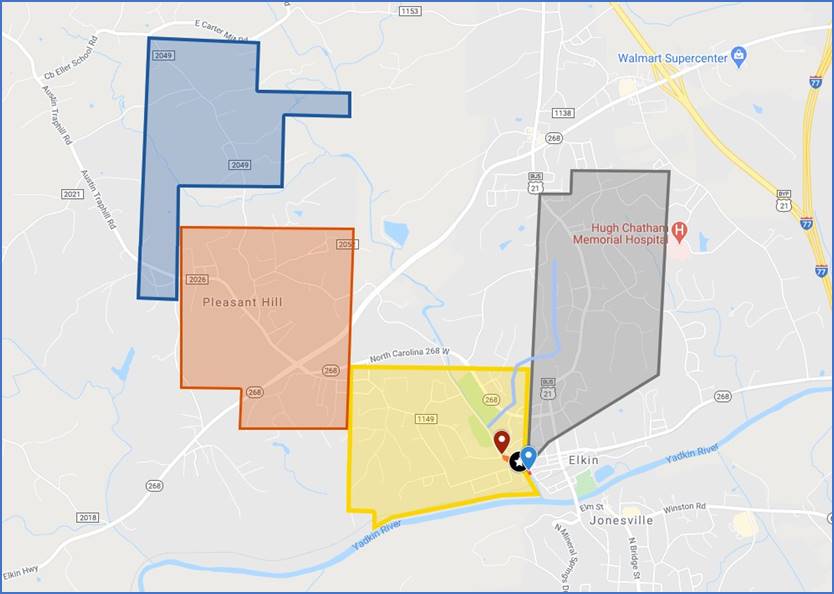

David Allen purchased four large land

grants. The two on the west were in

Wilkes County. The two on the east

were in Surry County. The iron works

was on the Big Elkin Creek near the southeast corner of the yellow tract as

shown above. The iron works, furnace, and forge

likely only occupied 10 or 20 acres. The

rest of his property was used for its resources. His workers needed a large area to search

for the best locations to mine for iron ore.

He also needed trees – lots and lots of trees! The iron works operation required a

constant supply of charcoal for two purposes.

One was to fuel a fire for “cooking” the moisture out of the rocks to

prepare them for the furnace. The

other was for the opreration of the furnace itself where the iron would be

smelted from the ore in a fire that reached temperatures of 3000° F. The charcoal was likely made at the

spot where trees were cut. The trees

would be burned in local piles, and the resulting charcoal would later be

transported to the furnace. I imagine

that the smoke from these fires could be seen from many miles away, serving

as a beacon to travelers making their way through the area. Perhaps on a clear day, the Moravians in

Salem could see – and smell! – the smoke produced by David Allen’s iron works

from thirty miles away.

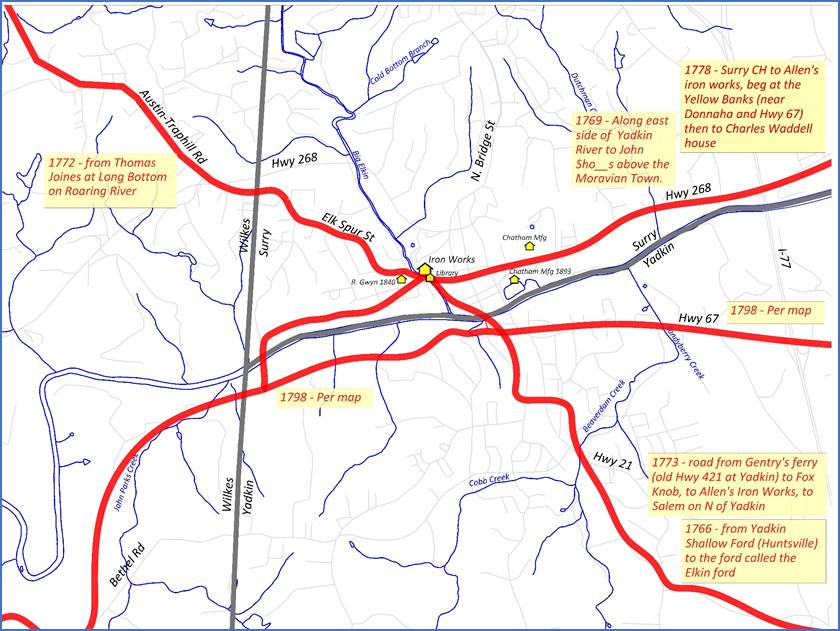

Roads led in all directions from the

iron works. Roads led east to the

Moravian settlement along both sides of the Yadkin River. There were two places to ford the river

near the iron works. It's unclear how many people worked at

the iron works, but it was more than a dozen.

In 1781, the NC House of Commons declared that “any twelve persons who

shall be employeed by David Allen & Company, in the business of the Iron

Works, shall during the time they shall be so employed be exempted from all

Military duties.” That’s a big deal! This was during the Revolutionary War when

all able-bodied men were expected to fight for their new country. The fact that twelve men were exempt from

military service indicates how important the iron works was to the

revolutionary cause. The iron works provided iron that was

needed to make war-time necessities including swords, canons, muskets, and

musket balls. That’s in addition to

everyday items such as cookware, hinges, nails, and parts for milling operations. As a vital part of society, it was an

industry targeted by the British. That

meant it needed to be fortified and protected from the enemy. One young man who was stationed at the

iron works was Elihu

Ayers. He had arrived from

Virginia in 1778 when he was about 17 years old. He later wrote that he had been stationed “at

David Allen’s iron works in the county of Surry, North Carolina, to guard them

and protect the surrounding neighborhood from the deprecation of the Tories

who much abounded in that section of the country.” He went on to say that he was frequently

sent out in search of Tories and robbers, and that he would always return to

the iron works, with “that place being the headquarters of the company called

the Iron Works Company.” This is quite a statement! Not only was the iron works guarded to

prevent attacks from the British, but it had become a gathering place for men

who were prepared to fight at a moment’s notice. It was a staging ground for men to be sent

out on expeditions to engage the enemy.

The best example of this was in 1780 when Col. Joseph Winston gathered

150 men near the iron works along the Big Elkin Creek. They made their way west along the Yadkin

River and met with others at Wilkesboro before the pivotal battle at Kings

Mountain. Entire books have been

written about the Battle of Kings Mountain, so I won’t get into the details

here. The important point to remember

is that it was a critical victory for the patriots, with Thomas Jefferson

calling it “The turn of the tide of success” that led to the eventual defeat

of the British.

After the war ended in 1783, things

must have become quieter at the iron works.

Soldiers and guards were no longer needed, and the immediate demand

for military supplies was lower than it had been during the peak of the conflict. David Allen was in his 70s, and perhaps he

felt like it was time to turn the operation over to a new owner. He might not have been in the best of health,

either. Back in 1780 he was injured at

the Battle of Shallow Ford at what is now the Yadkin and Forsyth County

line. The Moravian records at Bethania

state that “the elder Allen was in very bad case, though he was not in as serious

a condition as was reported.” David

Allen would have been too old to fight on the front line, so perhaps he was

driving a supply wagon when he was hit by a musket ball. He was transported fifteen miles away to his

friends at the Moravian settlement who treated his wounds. He was a patient for six weeks before he

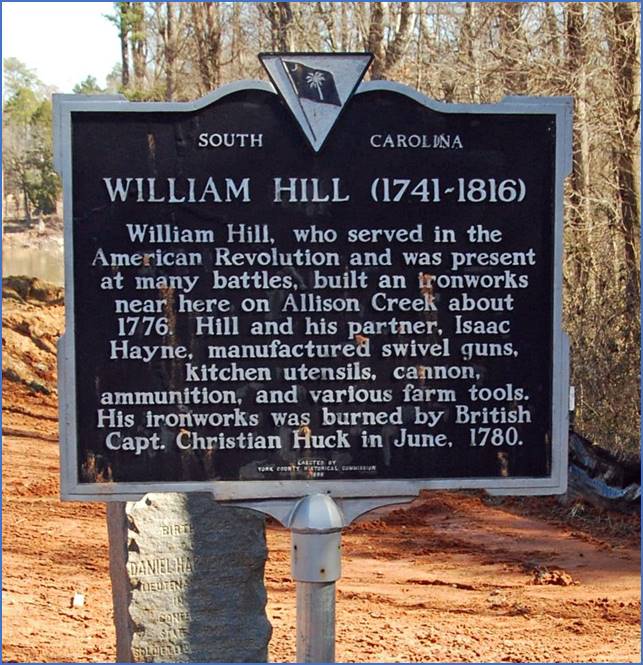

returned home. In December 1786, David Allen sold all

2,482 acres to William Hill of York Co, SC.

David Allen left Surry County and is believed to have moved to Georgia

to live with his son. William Hill had

been a Colonel during the war, and he an iron works of his own in South

Carolina. During the next 15 to 20

years, the iron works on the Big Elkin was owned and managed by a combination

of William Hill, Jonathan Haynes, and Obediah Martin.

The iron works was still in operation

in 1802 when the Surry County Court declared that at least 5,000 pounds of

iron had been made during the previous year at the old Iron Works belonging

to Hill and Haynes on the Big Elkin.

This made them eligible for free land from the state. However, by 1807 the operation had likely

come to an end. The half of the property

that was located in Wilkes County was delinquent in taxes for that year, and

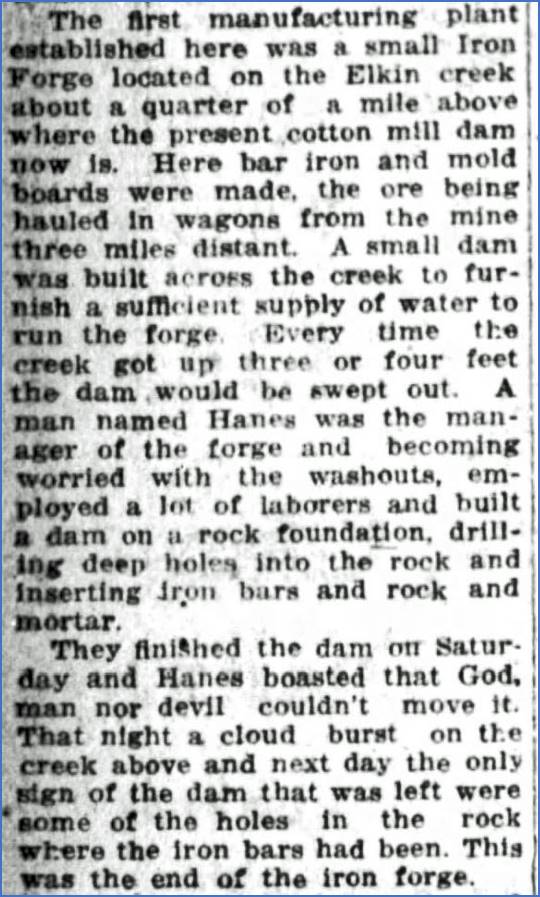

a portion was sold in 1809 to pay the debt. A story about the demise of the old

iron works was printed in the Winston-Salem Journal in 1922. It says that every time there was a

moderate flood on the Big Elkin Creek, the dam that provided water power

would be washed away. Finally, the

manager Hanes employed workers to build a dam with a rock foundation,

drilling deep holes into the rock and inserting iron bars and mortar. Hanes boasted that “God, man, nor devil

couldn’t move it.” But that very same night,

a storm came through and washed the dam away.

Only the holes that had been drilled in the rock provided evidence of

where the dam had been. As the article

says, “This was the end of the iron forge.”

Winston-Salem Journal, November 26, 1922, page

2C. The flood that provided the final blow

to the iron works might have occurred around 1805 based on the court

records. After 40 years of lumber and

iron ore production, the property remained idle for the next 30 years until

Richard Gwyn purchased the original 640-acre iron works tract in 1839. Perhaps he had visited the iron works as a

boy while it was still in operation, after all, he was born in 1796 just six miles

west of there. As an adult, Richard Gwyn

moved to Jonesville to raise his family, and he would have had a clear view

across the Yadkin River at more than a thousand acres of available land. Perhaps there were still remnants of the

old iron works visible along the bank of the Big Elkin – the remains of a blacksmith

shop, piles of unused rocks, or a chimney marking the location of an office. Perhaps the most valuable legacy left

by David Allen was a network of roads that led in all directions. Not only was there a reliable water supply

on the Big Elkin, but the fact that there were established roads meant that

Richard Gwyn could focus on his business instead of on the logistics of

getting material to and from his mill.

Creating new roads would have been costly and time consuming, but

David Allen and his successors had absorbed that expense decades

earlier. Richard Gwyn’s grist mill was

a success that soon led to his cotton mill, and the eventual establishment of

the town of Elkin.

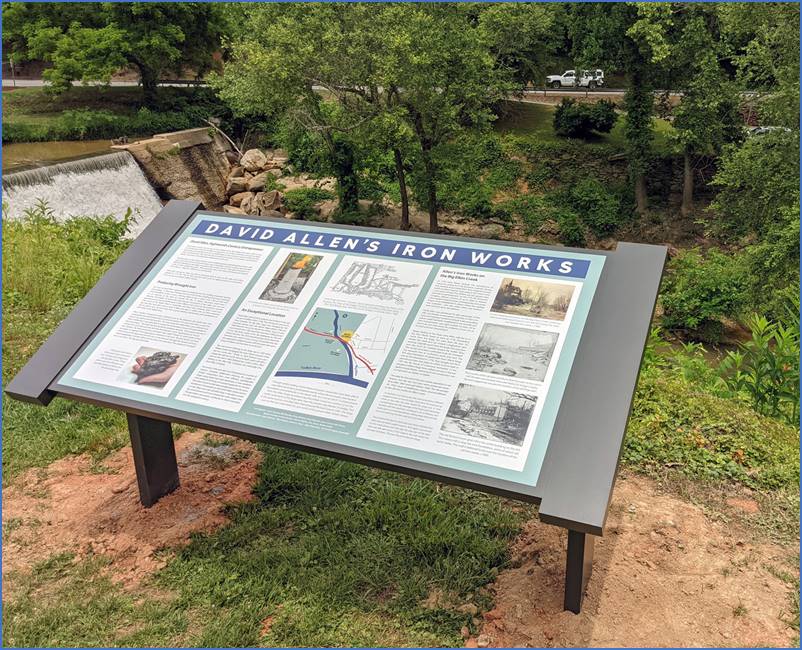

In 2021, a historical marker was

installed along the Overmountain Victory Trail overlooking the site of the

iron works to recognize the historical significance of the first industry in

Elkin. It was the culmination of research

by a group of history enthusiasts including Doug Mitchell, Gabe Mitchell,

Bill Blackley, and Jason Duncan. Much

more about David Allen can be found on my Elkin History page.

Comment below or send an email - jason@webjmd.com |